“What are they even feeding us?” and “Is this even fit for human consumption?” are a few questions you’ve probably heard when it comes to school lunches in America. Throughout the years, school lunches have become infamous for failing to ensure that students have the nutrition they need while gaining a separate reputation in failing at their other purpose to taste decent. Despite how overpriced other food sources located around our school are, they’re still largely popular due to the alternative being school lunches. But how did we get to this point? How have the school lunches served in the United States become known for being seemingly indistinguishable from prison food? In order to answer that, we must go back to where it all started and see what made school lunches what they are today.

While examples of school lunches have been around as early as colonial America, they were few and far between due to the lack of a standardized system. The first recorded example of a “proper” school lunch system was in Boston in 1894, which was developed by a scientist named Ellen Richards. Richards had previous experience with feeding the local community by creating a restaurant designed to make nutritious and affordable meals, which was why the Boston School Committee invited Richards to test a lunch program at multiple schools to provide affordable hot meals to students.

Of course, there were flaws with this lunch system, namely that the menu was very limited, consisting solely of fish chowder, crackers, bread and butter, and a bun. A larger problem, however, was the lack of kitchen or dining facilities needed to supplement the new system, which was especially noticeable in poorer areas. Students residing in these areas desperately needed a consistent supply of food, as it was unlikely that their parents could afford to supply them with something to eat during school. Despite this, these items alone totalled to 692 calories. Combined with the fact that the food was extremely cheap, costing just 10 cents, this program was still a massive success with overwhelmingly positive feedback from students and teachers alike. This program was funded partially by the city government along with the assistance of many volunteers and charities.

By the 1900s, school lunches started spreading to larger cities across the country, such as New York, Chicago, and Houston. These school lunch programs used the British school lunch program as a model for their structure and were developed carefully by nutritionists to minimize costs while maximizing the number of calories for increased learning potential. The spread of the school lunch system rapidly accelerated from there: by 1912, over 40 cities had lunch programs in elementary schools. These programs were able to serve over 600 thousand meals a year for only one penny per meal. However, there was minimal federal government funding, and since volunteers couldn’t afford to subsidize the program on a larger scale, they turned to the state government. In 1920, the New York City Board of Education financed 35 out of the city’s 500 schools, which set a significant precedent for government funding in regard to school lunches. With school lunches receiving more funding, it further evolved as in 1917 the menu for schools in Philadelphia consisted of Baked beans, milk, crackers, ice cream, vegetables, soups, creamed beef, macaroni with tomato sauce, and creamed salmon. While this wasn’t consistent with the menu of many other school districts, it paints a clearer picture of the increased diversity and evolution of school lunches since Richard’s first menu. Unfortunately, this increased government funding of school lunches led to “Americanizing” the immigrant population of the United States as no concessions would be made to cater to non-American food.

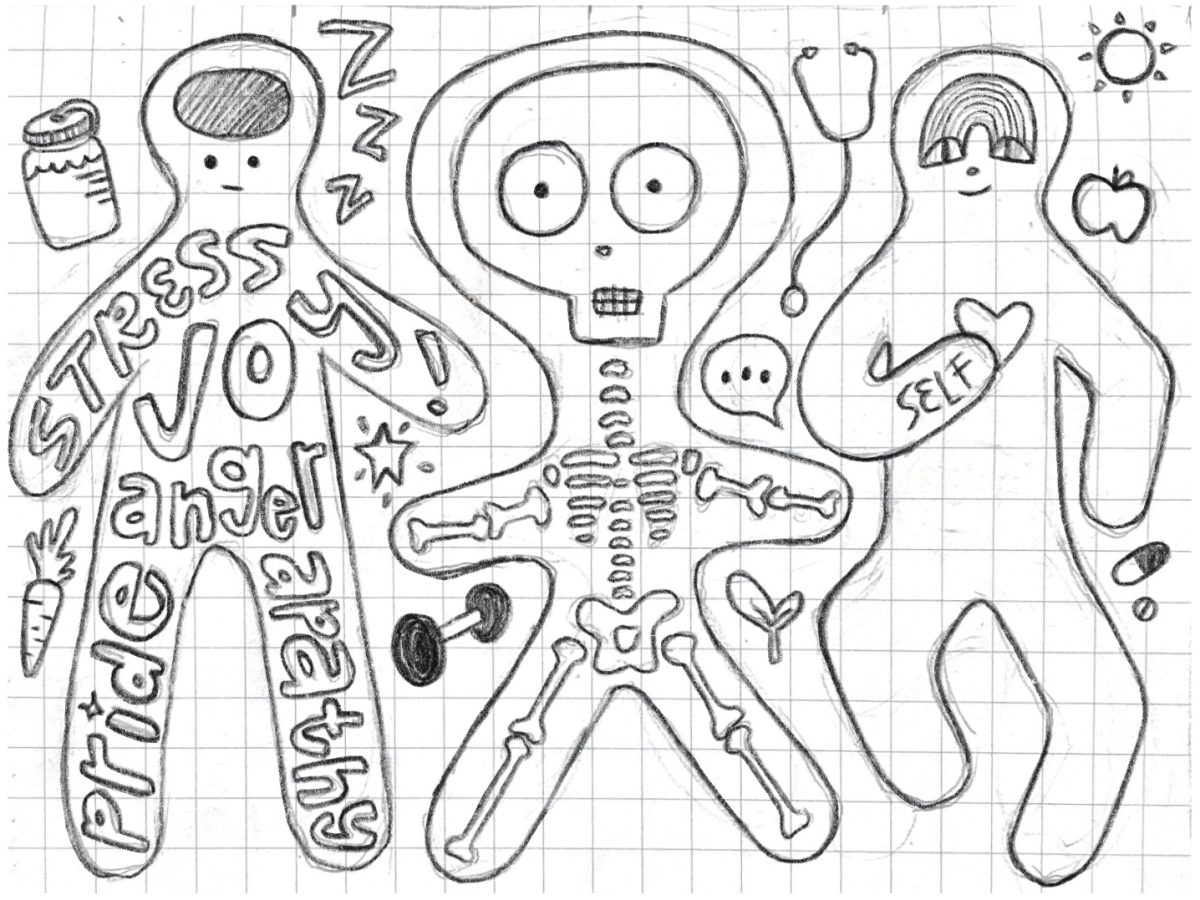

School lunch programs continued to evolve as they expanded across the country. However, many school districts still lacked school lunches as it was funded and maintained by city and state governments. That was until WW2 when school lunches became an issue of national security due to food scarcity during the war. In 1946, President Harry Truman signed the National School Lunch Act which provided low to no-cost school lunches to children in need through federal subsidies. School lunches declined in the 1950s as the federal government sought to lower food costs by eliminating a lot of the nutritional quality and replacing it with more calorically dense food. Fruits, vegetables, and lean protein were the main targets and were replaced by options such as cheese and sausage meatloaf.

Despite the misstep during the 1950s, school lunches improved during the 1960s with several major developments that are still seen today. This includes the school breakfast and the special milk program that gave every student milk along with their meal in 1966. Alas, these benefits were overshadowed by more problems and controversial changes that were passed from the 1970s to the 2000s. Schools started to sell fast food such as hamburgers, chili dogs, and fried chicken, which coincided with a government report finding that school lunches “fell far short of providing minimum nutritional standards” as they were high in fat. The Reagan administration reduced federal funding for school lunches, which shrunk portion sizes, cut eligibility for free and low-cost lunch, and lowered the standard for what could be labeled as a vegetable (an infamous example of this was labeling ketchup as such).

As if that wasn’t bad enough, many schools outsourced their programs during the 1980s to private companies to compensate for the federal funding cut. This led to further cuts to the nutritional value with an increase in fast food, as well as frozen food such as chicken nuggets and pizza. This downhill trend was so dire that the Department of Defense was tasked to help schools using a program designed to provide vegetables and fruits to the army.

By the 2000s, it was estimated that 50% of cafeterias offered meals from restaurants like McDonald’s, Chick-fil-A, and Little Caesars. Then came the Obama administration which passed several acts in the 2010s including one that offered free lunch and breakfast to every kid in school where 40% or more of the student body was low-income. Michelle Obama launched the “Let’s Move!” campaign to encourage healthy lifestyles in children and families. “In the end, as First Lady, this isn’t just a policy issue for me,” said Michelle Obama about the “Let’s Move” Campaign. “This is a passion. This is my mission. I am determined to work with folks across this country to change the way a generation of kids thinks about food and nutrition.” What better way to start than with school lunch? Alas, the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act was passed, shaping school lunches into what we see today. The federal government increased funding and made vegetables and fruits more commonplace in lunchrooms. Food standards were raised, and even more students were given access to school lunches.

However, the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act was not enough to reverse the downward trend of school lunches. Fast food and low standards are still present, contributing to America’s high obesity rate. School lunches are also largely unpopular and contribute to food waste. A study made by Pennsylvania State University found that 27% to 53% of food served was thrown away. With all the numbers against it, you might wonder “Why not abandon the program altogether?” Despite the controversy and criticism school lunches have faced, these programs are important because they serve over 4.9 billion free or low-cost school lunches each year to millions of students across the nation. The program might be the only thing that feeds some students and abandoning it would be disastrous.

Though the future of school lunches might seem grim, the path to fixing it couldn’t be clearer. Funding has always been the main opponent of school lunches since their creation and was the cause of their decline since the 1960s. Increasing funding would allow schools to include higher quality and more nutritious meals while expanding the number of students who could receive it. Funding might not eliminate all issues of the program, but it would be a massive step in the right direction.

In conclusion, the history of school lunches in America has been one of evolution, experimentation, and ultimately, decline. The tragic decline of this program has affected the millions of students that both eat and don’t eat the food including us in HSMSE. According to Feng Yi, a person who frequently eats at the NAC, “milk, pb&j , the thing where you scoop meat with chips (tostitos) are good and the bad things are pizza and vegetables.” This paints a clear picture of how simpler items are more favorable due to the consistency of them. The more complex items lack funding and get watered down to fit in the budget. Therefore we must let our voices be heard and complain about the state of school lunches as although we should be grateful of the programs existence, this is our only weapon against the decline of a program millions of students depend on.