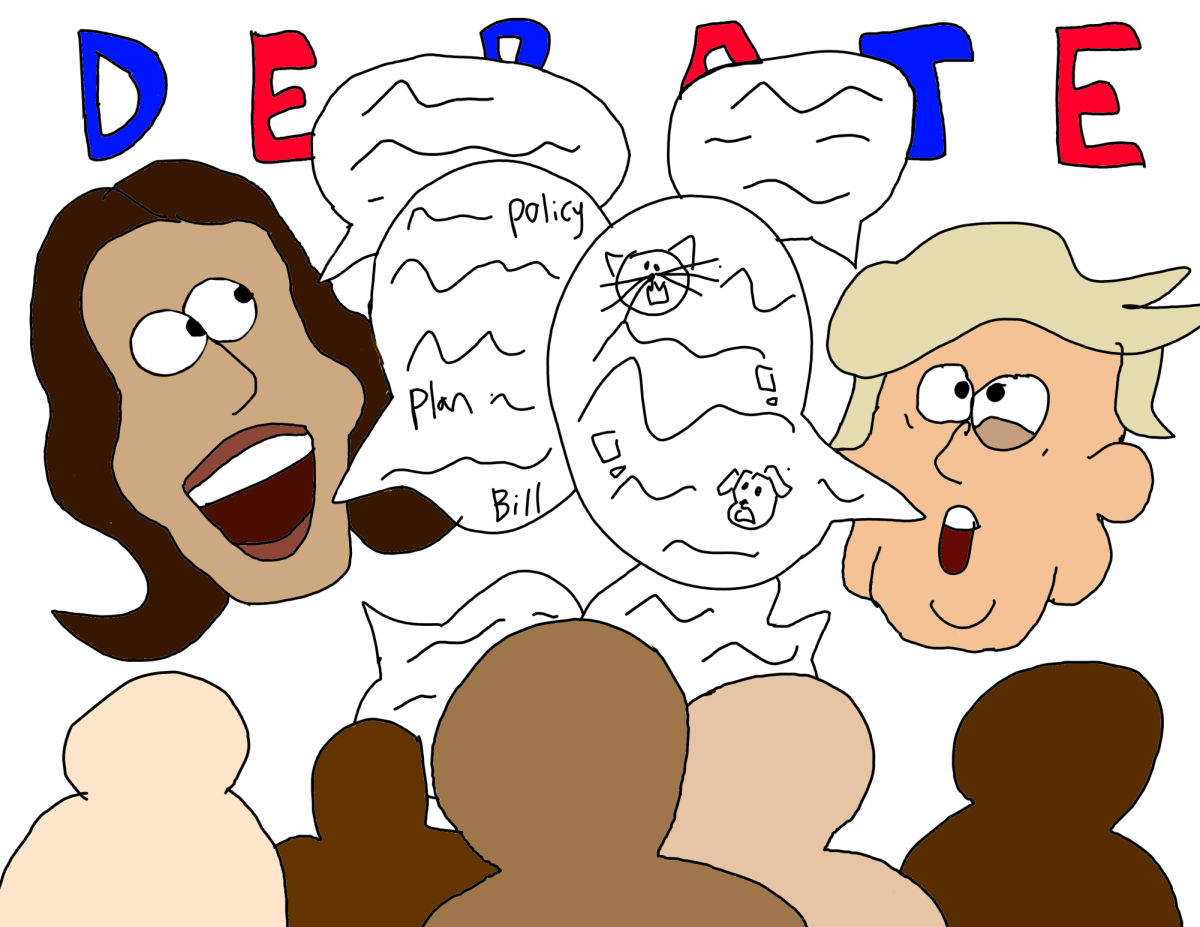

Many of us have heard of the Second Avenue Subway project, the infamously over-budget transit idea that opened in 2017. This was followed by a string of unfortunate events that resulted in the former governor, Andrew Coumo, declaring a state of emergency i

In fact, Phase 2 is already long underway, although sadly only in the planning stages so far. The plans dictate extending the current tracks on which the Q line operates up to East 125th Street and Lexington Avenue to connect with the 4, 5, and 6 trains and Metro-North, with intermediate stations at 106th Street and 116th Street. However, the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) is considering several options for further extensions, including a crosstown line under 125th Street with various potential western terminals. More about Phase 2 will be detailed in the next issue.

As for Phase 1, it has many benefits and issues, but truly understanding it first requires a look into the past. The history of the Second Avenue Subway goes back all the way to the 19th century, when the Second Avenue Elevated Line was first proposed. Opened in 1878, the Interborough Rapid Transit (IRT) Second Avenue Elevated Line served the east side of Man

n the New York City transit system. This led to more funding for the system in general, thanks to Cuomo’s and former head of the MTA Andy Byford’s lobbying. But what if we told you that that was only Phase 1? That there will be more to come (eventually)?

hattan between City Hall and East Harlem, mainly along Second Avenue. It was bought by the City of New York in 1940, when the three rapid transit systems operating in New York City were unified under one label, the New York City Transit Authority (NYCTA). Things started to change for the city in the 1940s and 1950s when the NYCTA began to see a continual decline in ridership and funding. This was largely due to the proliferation of personal motor vehicles and construction of highways all throughout NYC. Numerous elevated lines were eliminated and demolished in the 1940s and 1950s, including the Second Avenue Elevated in 1942, and the Third Avenue Elevated in 1950–55. The Second Avenue Subway underground line was planned before demolition of the elevated, and its planned co

nstruction was the reason why the Second and Third Avenue elevateds were demolished.

No discussion of public transportation in New York City is complete without discussing the 1970s and 1980s. These decades were without question the worst in the city’s history, with the city going bankrupt in 1975 and the federal government refusing to bail the city out. During the 1960s, a period of perpetual decline, there was overcrowding on the Lexington Avenue lines (today’s 4, 5, and 6 trains), so the NYCTA decided to build a new line to relieve it. A few short tunnel segments for the Second Avenue Subway were built in the early 1970s, but the budget ran dry in 1973, and we were left with four tunnels not connected to each other or any existing tracks, and

thus they were utterly useless. Until 1988, in some run-down office building in Downtown Brooklyn.

Four interns sitting at a desk. One, Peter Cafiero, suddenly has an idea. Why not build the Second Avenue Subway? Cafiero had been fascinated by transit in New York City from a young age, and it was a dream come true to work for the MTA (successor to the NYCTA, renamed in 1968). This idea set the wheels in motion for the Second Avenue Subway to finally be fully built, fifty years after it was first proposed.

Twenty-five years of environmental reviews later, ground was broken in 2003 on Phase 1 of the Second Avenue Subway, which extended the Q train from 57th Street and 7th Avenue to 96th Street and Second Avenue. The original plan was to have the entire subway line, from 125th Street down to Hanover Square in the Financial District, co

mpleted by 2020… but as will be explained here and in the next issue, that didn’t exactly go according to plan.

Phase 1

Phase 1 in general was a very good project, as it provided alternatives to the Lexington Avenue lines (4, 5, and 6 trains) and increased accessibility to the East Side. This brought new transit options to the Upper East Side and allowed for economic de

velopment, but the project was over budget. The estimate claimed it would be finished in 2012 in time for the Olympics, with a price of $3.8 billion.

Phase 1 was opened on New Year’s Day 2017, five years late, at a cost of $4.45 billion, making it the most expensive transit project on a per-mile basis in history. The deadline for completion was pushed back so much that there became a joke that to the MTA, a deadline is a deadline to set a new deadline.

Some reasons for the high price tag are that it was entirely new, and construction in Manhattan is generally very expensive for a multitude of reasons. Nevertheless, most people agreed it was overpriced. The station mezzanines are immense, and this undoubtedly contributed to the inflated cost. The extension was built by tunneling under Second Avenue, which came with issues of its own. One major problem that arose was that the MTA wanted to keep at least part of Second Avenue open for traffic during the entire construction period, which led to them to digging up half of the avenue, putting all the equipment in the hole, digging up the other side, moving everything, and then repaving the side they’d just been operating under.

Other reasons for the massive price tag include high land acquisition costs. The subway needed ventilation shafts, and so the MTA had to buy land to build them on and demolish the existing buildings on those lots. The entrances as a whole are very grand, often incorporating glass canopies over the stairs or escalators. Similarly, large numbers of elevators are prevalent. This grandeur is exemplified by the five elevators at the 72nd Street Station.

Overall, Phase 1 contributed heavily to reducing overcrowding on the 4, 5, and 6, and stimulated the Upper East Side economy, and that of the whole city and state, by extending the Q line and generating many, many jobs for construction. It provides major benefits to the communities it serves, who had previously only been served by buses or the perennially overcrowded 4, 5, and 6 lines. While the line is undoubtedly vital, its stations are rather large and usually feel rather empty in spite of each seeing over 100,000 daily riders. It took way longer than it was originally supposed to, but it was nonetheless a wait well worth it for the benefits it delivered. Phase 2 is supposed to continue these trends.

While many may scoff at these expansions, they’re a sign that the government is starting to care about public transportation again. Recognizing their past mistakes, funding is being pumped into the subway with help from President Joe Biden’s infrastructure deal. More money will help reduce wait times, improve maintenance, and fund new buses and trains. The Second Avenue Subway is the start of a new era for the MTA.