For me, HSMSE was never the obvious choice. I was always an artsy kid from a family where art was the language we all spoke. I was scribbling before I was talking. And for my parents, one a graphic designer, the other a painter, a STEM-based school wasn’t something they would have ever imagined for me. When I was younger, I spent endless hours drawing houses, families, and characters, fascinated by the possibility of turning lines into stories. I loved to read and write and I thought maybe I’d become a teacher. But then I found science. I remember watching Contagion, a movie about a fictional virus that ravages the world (this was pre-Covid), and experiencing a new sense of wonder. Seeing the urgency of the scientists as they rushed to find a vaccine, and understanding that science could save lives, I felt that I had found my calling.

Now I think I would rather spend my hours in a research lab. But I am still that same kid who likes to draw sometimes, and art undeniably colors my perspective of the world. I will never be able to walk through this city without feeling bombarded with drawing ideas: the burly security guard in the tiny golf cart or the lady balancing a chair on her head. Art even shapes how I think about science. There is unparalleled artistry present in each and every one of our cells, from the simplicity of a strand of DNA to the magnificently complex proteins it encodes.

Here at MSE, I have the opportunity to pursue my research interests, and in our community, I have found a home. Our classes are interesting and challenging, and our teachers are arguably some of the best in the city. Yet, I also can’t help feeling that there’s a piece missing from our education. When deciding on MSE, I realized that it would be the end of my in-school art education. I knew going in I would have to pursue art elsewhere. Last year, I found myself taking Saturday painting classes at The Cooper Union with similarly alienated art kids from Brooklyn Tech. I wondered why all of these STEM-focused schools were sacrificing art. There are so many of us, STEM kids who make art in their free time, why is there no real space for us during the school day?

The city requires every high school student to earn two art credits before graduating. At MSE, one of these credits is fulfilled by drafting, vaguely described on the school website as a course “designed to prepare the students for college level engineering work.” I think it’s fair to say that while drafting includes some drawing, it’s more of a technical class than one that allows for any creativity. Apparently, through a long-term agreement with the DOE, we are allowed to call drafting “art.” HSMSE provides us with a unique opportunity to pursue a high level of architecture early in our high school careers and drafting is a necessary component of that education. It would be unfair to assume that all MSE students are even interested in pursuing a traditional visual arts course. At our school, it can be difficult to get many kids to skim a sonnet, let alone pick up a paintbrush. In this way, drafting and architecture encourage STEM kids to dip their toes in the world of art, under the guise of drawing for the sake of “engineering.” However, drafting and architecture courses are not an acceptable substitute for the visual art classes that allow those who are truly interested a space to express themselves creatively and unwind.

For many student artists, the art elective, taught by the multitalented Mr. Pedroso has provided this space. Eli Gologanova, a sophomore who took the elective this fall, said that they chose art because, “as an artist at a STEM school, there really aren’t that many opportunities to draw.” The art elective, which focuses on the development of technical drawing skills in the fall and painting in the spring, is truly our only visual arts class. I recently stopped in to admire the student art tacked up on the walls of the architecture room where the art elective is held. There are a series of colorful collages to accompany the poem Sympathy by Paul Laurence Dunbar and countless charcoal still lifes. But what I found the most striking were the surrealist mashups of household objects and animals, including a lotus teapot with a seahorse spout and a gloomy cow with a fork for a head. Not only were the pieces skillfully executed in white pencil, luminous against the black paper, but they were also remarkably creative. However, in its emphasis on technique, many felt that the art elective did not provide them with enough opportunity to express themselves creatively. As Eli explained, the course “didn’t have the freedom of a free-draw or the learning experience of a taught course,” but they “did enjoy having a quiet part of the day devoted purely to drawing.” And the latter is important. While the art elective may not be perfect, it’s a start. It gives those who pursue and are passionate about art a time and a place to be artists in a school where they are the exception.

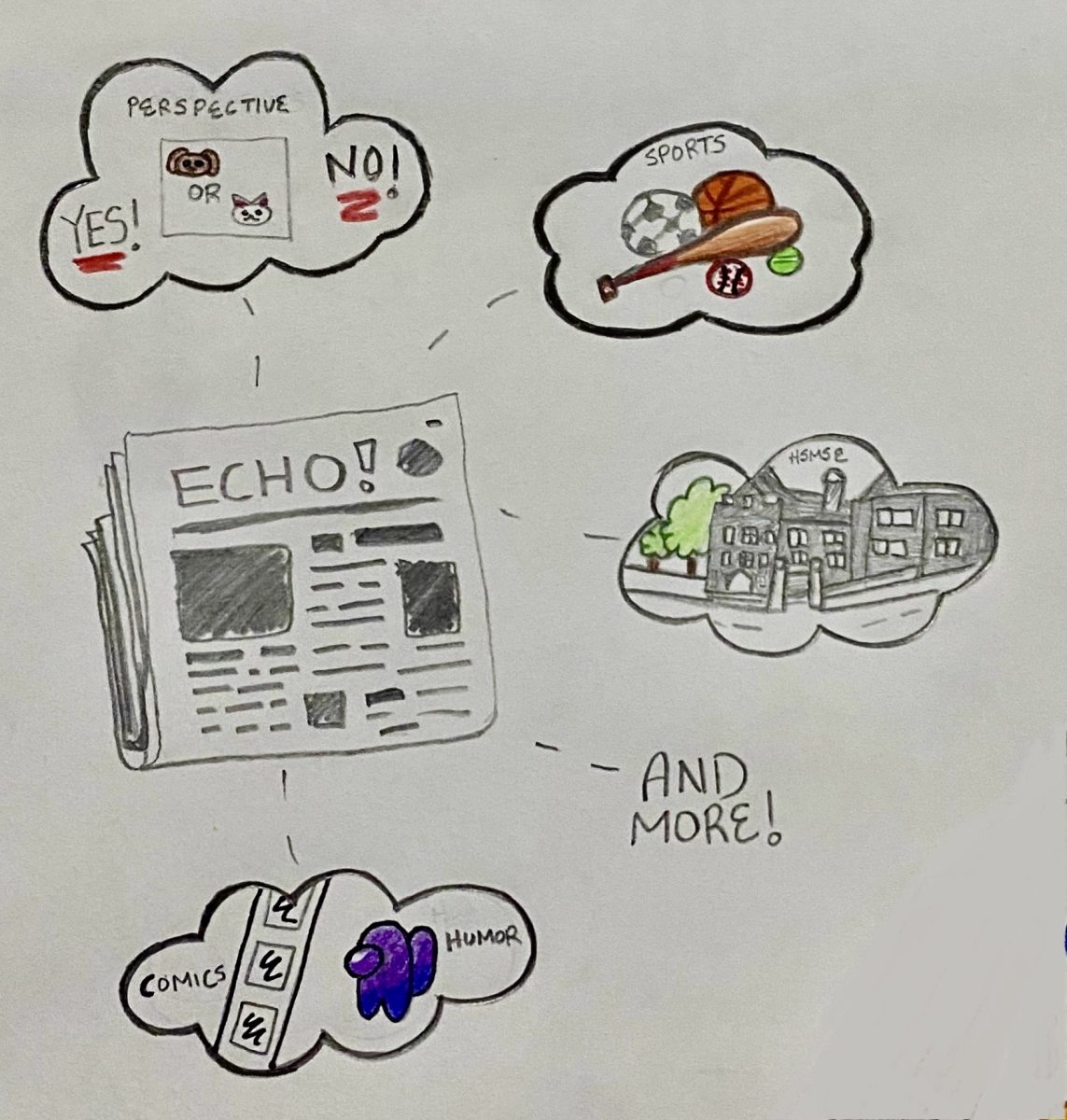

Our second art credit comes from music, and unlike visual arts, we do have a pretty extensive music program. In my efforts to scope out art around the school, I took a trip down to the music room to chat with Ms. Brown, our wonderful music teacher. To fulfill our second art credit, sophomores are required to take a semester in music, a class centered on composition. I really enjoyed music class because of the creative freedom it allowed, unique from my other classes. Students can also choose to take a music elective: either classical guitar or jazz band. And between acapella and the chamber music club, the c-floor always seems to be humming with music. Perhaps this is because, as Ms. Brown puts it, “there’s this natural correlation between math and music, and we have brilliantly talented students here.” With its emphasis on time signatures and patterns, music has naturally found a place among us math kids. Music has the ability to make complex concepts more memorable and easier to understand. From the ABCs to the quadratic formula song, music has always played an important role in our education. But the benefits of art education extend far beyond music.

HSMSE has a new art-based course this year. The A.P. Art History course, taught by Ms. Rasuk has so far been a big hit among students. Ms. Rasuk told me that her students “do a lot of the research on their own and the discussions are fun. They sometimes get intense.” Aaron Wang, a junior in the course this year, adds that “it’s just fun to talk about because you see patterns, you see stylistic features, and it’s just really interesting to see how different kinds of art evolve.” Good art education does not necessarily require art-making; the critical thinking skills that students develop through analyzing and discussing are just as important. Aaron describes that in art history, students learn “techniques for understanding different elements of an art piece. You have a frame for what’s actually happening there, and then you can explore and make connections on your own.” On a broader level, as Ms. Rasuk explains, “art history is how you understand society, how people think and what people have gone through. It’s an intricate part of history, because you actually have a product that tells you what happened in this period and the reason it happened.” This way of thinking is not limited to topics like history or anthropology, but it can actually allow us to better understand STEM.

A well rounded education in the arts can help us to think more critically about science and technology. STEM has been at the center of most conversations about education in recent years, with the assumption that if we set young people up with STEM skills, they will be guaranteed good jobs. This overemphasis on STEM has led to major sacrifices in the arts and humanities. Yet, there is growing research to demonstrate that cognitive diversity, or having different kinds of expertises and experiences (including those in the arts) plays a necessary role in technological innovation. As new technologies increasingly weave their way into every aspect of our daily lives, it seems there will always be a demand for computer scientists or software engineers. But the advancement of technologies such A.I. and social media also inevitably bring larger philosophical and ethical issues to the surface, issues that are not in the skillset of coders or engineers to address. We need to understand what role A.I. will play in our relationships, education, and security. How will we distinguish between the human and the machine? And as we continue to edit our genes, who will draw the line between life-saving genetics and eugenics? This is where art comes in. We need artists and art-thinkers as well as STEM innovators, and better yet, those that can be both. And in recent years, conversations around STEM education have added art into the mix, shifting the focus over to “STEAM” instead.

Art is a useful tool in science for modeling and communicating complex ideas. From using artistic renderings to model the binding of the spike protein to the human receptor in understanding the pathogenesis of COVID-19 to illustrating deep sea creatures that otherwise would never have been visualized, art and science are inseparable. Eli says it well. To them, “science may be how I make sense of the world, but art is how I express that interpretation.” On a personal level, I always find myself doodling during Sinai classes to better understand the content. Drawing and redrawing that same double-stranded DNA helix dozens of times before I could finally grasp how the backbone twisted around a central axis apart from its own. Using art as a path to understanding through visualization. Being an artist and aspiring scientist, I think about how these two seemingly separate parts of my identity might intertwine. In designing for Dr. Dragon, our school’s STEM magazine, I have come to understand that at the intersection of science and art there is communication. I have had to think about how to best represent and amplify scientific writing through an artistic composition of images and text.

Despite the clear overlaps between STEM and art, students have often had to take the initiative when it comes to art within our halls. From the quirky student murals on the c-floor to the doors still covered in crafty valentines day displays, chemistry pickup lines included, MSE kids have an undeniably unique artistic flair. This fall, the halls were decorated with various beautifully designed and colorful flyers, requesting student submissions for MSE’s new art zine. With a great name, The Big Mac became our first art zine (as far as I know), thanks to seniors Lily Yan and Winnie Ng. “It all started with me and Winnie being the only two seniors in our gym class,” Lily recalled. “I didn’t know Winnie very well, but we were talking and realized that we both liked art… We wanted to encourage other people to make art.” Although these posters were up for a while, unfortunately there weren’t many submissions. But they managed to publish a first edition nonetheless. Their posters have since been taken down and The Big Mac has gone on vacation, but the importance of it couldn’t be clearer. As Lily explains, “there wasn’t very much opportunity for people to share art and learn from each other and have a community. That was our idea and that has not played out, but maybe in the future.”

Art was a central part of my childhood. Many weekends were spent at museums, galleries, or the studios of various family members. When I wasn’t in school, I was always drawing. But in middle school, I stopped calling myself an artist. With a combined insecurity at my lack of technical skill and a growing interest in science, art was forced to the background. Nowadays it is rare that I get the chance to really sit down and make art, apart from my occasional doodles during class. Yet I have started to call myself an artist again because I have realized that it isn’t talent, or practice, or even the making of art that makes someone an artist, but it’s how they look at the world, how they move through it and how they interact with it. I am inspired daily by other artists that push the boundaries of my thinking and shake everything up. The student artists I spoke with opened my eyes to the true importance of art. Like many people, I often find myself questioning what a few seemingly random splatters to a canvas could do to improve the world. As Lily described,“I’ve kind of always made art but I never took it seriously, it was just a hobby, but my attitude towards it has changed. Now I’m starting to think about how art can spread ideas and have an influence.” Art is a universal language, a tool for self-expression and communication found in every human civilization since we lived in caves. Its importance is so ubiquitous that I think it often gets forgotten. But for all of us, those that make art, admire art or even claim to “hate” it, art plays a crucial role in our lives. As an artist, Eli hopes that “someday I’ll be able to give people the solace art has provided me.” Perhaps someday MSE will allow its students more room to express themselves openly and creatively, but for now it’s up to us, the students, to create that space for ourselves.