Disclaimer: Although cisgender women are the primary group affected by reproductive healthcare issues, transgender and intersex people are also affected. This article does not intend to exclude any identities.

Abortion rights are a remarkably controversial issue that Americans have very strong opinions on. Whether it’s a TikTok, a speech from a politician, or a news story (maybe even one published by The Echo), there always seems to be a focused and fiery debate over the topic. However, with so many people choosing sides, what started as a life-saving medical practice has been twisted into something much more political. Suddenly, control over one’s own body violates human rights policies. Fighting for your own life translates to fighting the law. Whether or not you support abortion rights becomes a deciding factor in elections. Whether or not you support abortion rights is an extension of your religion.

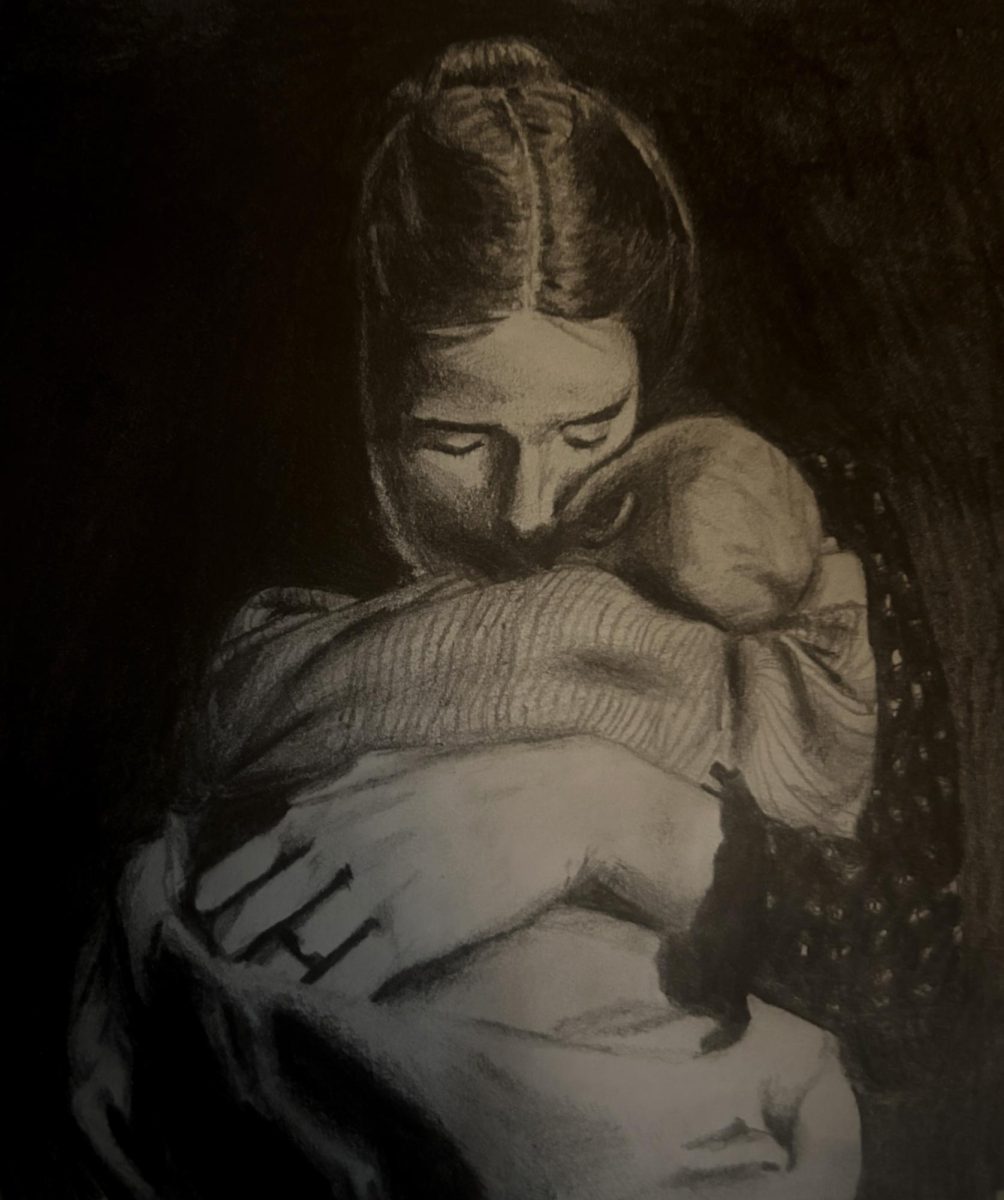

Ultimately, with all the chatter about the legality and “morality” of abortions, people seem to be forgetting that abortion wasn’t intended to be such a polarizing topic—it was brought to the attention of the United States because women and children were dying due to unsafe pregnancies. Case in point: From 1900 to 1953, over 800,000 women died in childbirth alone. This number doesn’t include how many women died via combat deaths, illegal abortions, homicide, death after pregnancy, etc. Back then, the fight for legal abortion wasn’t about politics; it was about preventing unnecessary deaths and improving reproductive health for the nation. That’s why, when Roe v. Wade (1973) legalized abortion, maternal mortality rates declined by more than five times.

Yet today, as the debate around abortion intensifies, maternal mortality continues to be a crisis that is overlooked, especially at the national level. The United States has alarmingly high maternal mortality rates, with approximately 33 deaths occurring for every 100,000 live births. This rate is more than four times those of other developed countries, such as Japan, Sweden, and Norway. Even more troubling is the stark racial disparity: Black women are three times more likely to die from pregnancy-related causes than white women. But why does this happen? And how do we stop it?

Unfortunately, what was once a clear answer has been muddied by recent events.

To help explain the logistics of maternal mortality, I interviewed Dr. Tara Shirazian, a licensed OBGYN and the founder and president of Saving Mothers, an organization dedicated to reducing pregnancy-related deaths worldwide. According to her, there are many ways a pregnancy becomes more risky for a mother.

“We really define maternal mortality as the death of a mother either during pregnancy or in the immediate postpartum period,” says Shirazian. “But postpartum can extend up to 30 days with the formal definition of maternal mortality, since events like blood clots and other pregnancy-related medical issues can have a delayed effect. Sometimes we see death further out due to preeclampsia or pulmonary embolism … But the most common cause of maternal mortality around the globe is postpartum hemorrhage.”

When a woman is pregnant, her body will undergo significant adjustments as a result of having to essentially take care of two living beings. Not only do the functions of the heart, lungs, kidneys, and immune system change, but blood flow also increases throughout the body. These effects are even more drastic for those who already have health conditions such as high blood pressure or diabetes. While they are necessary for the development of a fetus, they can lead to potentially fatal complications such as infections (e.g., sepsis) for the mother, as well as ectopic pregnancies (when a zygote develops in the fallopian tube rather than the uterus).

On the other hand, preeclampsia (high blood pressure in pregnancy), pulmonary embolisms (when a blood clot travels to the lungs), and postpartum hemorrhage (when a woman bleeds to death at the time of delivery) are a little different because they are more common pregnancy-related problems.

“Pregnancy complications are something that we treat all the time here on our labor and delivery floors,” says Shirazian. “They’re what we would call preventable causes of death.”

In fact, more than 80% of all maternal deaths are preventable. Which begs the question—if the United States has the tools to take care of pregnancy complications, why are so many women dying? Dr. Shirazian suggests that part of it is a universal lack of trust in the healthcare industry.

“It [partially] has to do with the lived experience of patients going to the hospitals and not being seen and heard, which I’m sure you’ve heard a lot about in the media, but it’s a real thing. If you go to the doctor and you say, ‘I don’t feel good, could I have a problem?’ And your doctor says, ‘You’re fine, stop complaining,’ and doesn’t actually listen to your issues or what you have to say, you’re not going to come back to that doctor with a new issue, right? You’re going to avoid, you’re not going to trust, you’re not going to come back, and you’re not going to be part of the healthcare system.”

However, most of the discrepancy comes from numerous barriers within the hospital. These barriers come in many different forms, but overall a significant amount of black women face institutional bias by providers. Some patients, especially women of color, may have their symptoms undermined or ignored— even if they have evidence of a serious problem. A prime example of this is what happened to Serena Williams: In 2017, she had an emergency C-section, but after giving birth, felt a shortness of breath. She immediately knew that she was struggling with a pulmonary embolism due to her prior experience with blood clots. With her life on the line, she exclaimed that she was going to need a CT scan and blood thinner—and was met with the initial response of reluctancy. In an interview with Vogue, Williams remarked that at first, her nurse told her that “her pain medicine might be making her confused.”

“She [Williams] had every resource; not only every resource, but was already educated on the issue and told her physicians that she thought she had a PE [pulmonary embolism],” says Shirazian. “So it’s literally crazy when you think about it, that this could actually happen. She’s a very good example of the fact that it’s not just economics, poverty or education that are risk factors; it’s race as well.”

With so many variables to keep in mind, it seems exceptionally challenging to come up with a solution that addresses all aspects of maternal mortality. In a perfect world, there would be no bias, and everyone would have equal access to good hospitals. Obviously, the chances of that happening are awfully low, especially in the United States. But there is one method of preventing maternal mortality that has been proven to be effective throughout the decades: abortion. There is unquestionable evidence that abortion availability and maternal mortality are interconnected, most notably the fact that almost half of all pregnancies are unintended. What better way to not lose your life via an unsafe and unplanned pregnancy than to not have the pregnancy at all?

Despite the evident correlation, the Trump administration remains anti-abortion. In just four months of presidency, the American government has already shut down all research initiatives dedicated to reproductive health and racial equity and pulled tens of millions of dollars in family planning funding. Luckily for Saving Mothers, most of their funding comes from private donors and therefore is not subject to government change. Others, though, aren’t as fortunate.

“I have many colleagues that have had federal and state grants revoked,” says Shirazian. “Not having support behind women’s healthcare, from abortion care through pregnancy and beyond, is devastating for women’s health research and access to care. It doesn’t prioritize women’s health at all. It’s been horrible. And all we can do is keep doing what we’ve always been doing.”

Ironically, even after the overturn of Roe v. Wade in 2022 (and the events that have followed), Saving Mothers has been putting in more work than the U.S. government to lower maternal mortality rates on a national and global scale. Dr. Shirazian and her team have placed emphasis on providing access to family planning, contraception, IUDs, education, doctors, and other resources to countries such as the Dominican Republic, Kenya, Guatemala, as well as the United States. They’ve cooperated with ministers of health about reproductive health funding, and have created the mPOWHER Kit for mothers specifically living in New York City. However, more work from everyone, not just Saving Mothers, needs to be done in order to put a larger dent into the issue.

From a realistic perspective, it’s not going to happen any time soon. It’s certainly not going to be easy.

But that doesn’t mean we should give up on the fight. Every life lost to preventable maternal death is a tragedy that could have been avoided with proper care, attention, and access to the right tools. While the Trump administration may not be prioritizing maternal health the way it should, organizations like Saving Mothers are pushing forward to fill the gap of awareness (follow them on Instagram at @savingmothers).

“It’s not a political conversation at all. It’s healthcare,” declares Shirazian. “It’s part of allowing women human rights, human dignity, prioritization over their own bodies, their ability to make their own healthcare decisions. It is part and parcel of women’s health. It’s for no one else to decide and never has been.”