A sample of my TikTok feed: friends crafting a “college rejection cake” to transform their pain into sweet indulgence; a review of the perfect white T-shirt (no, really, the perfect one); and a dramatic edit of stock market graphs and recent news headlines on Trump’s tariffs, captioned “#recession.”

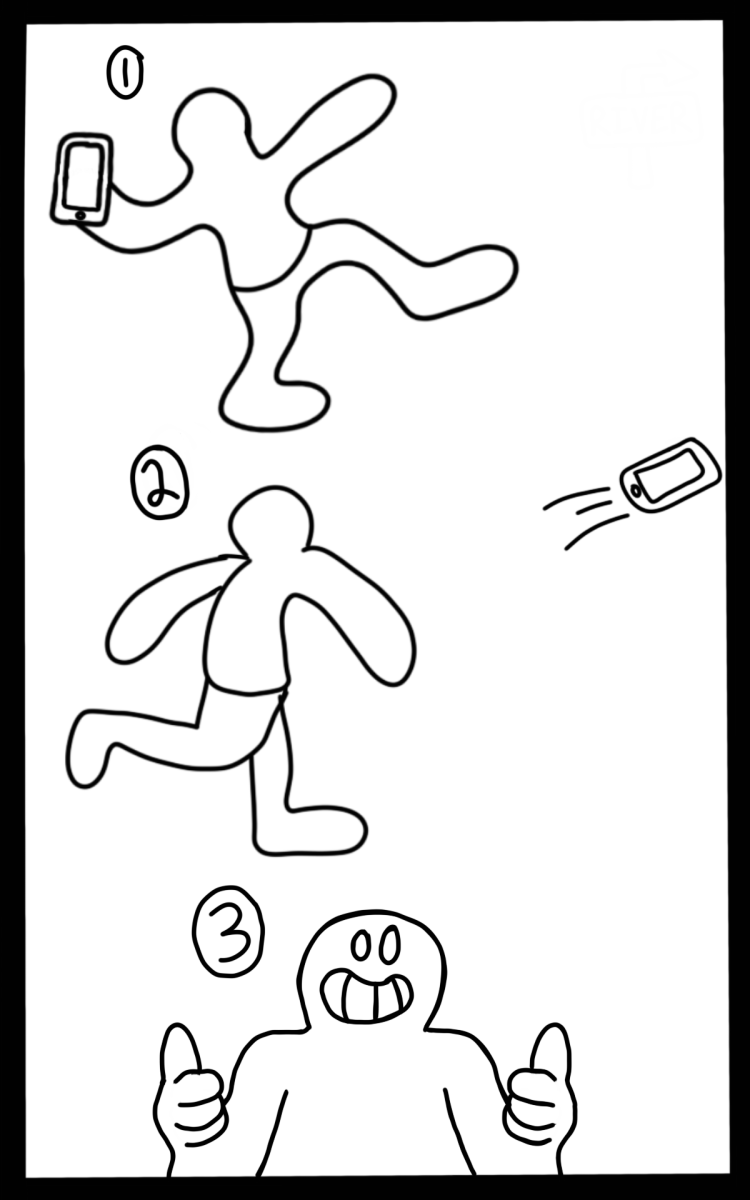

As we come of age in an increasingly chaotic and digital world, social media appears the perfect source of fulfillment and connection. We seem to control the content we see, and curate ideal representations of our lives; validation from others can be conveniently measured with likes and follows. When the stressors of real life are too agonizing to bear, our phones can provide a simultaneous escape from—and outlet for—our shared struggles. However, this pattern only perpetuates our misery.

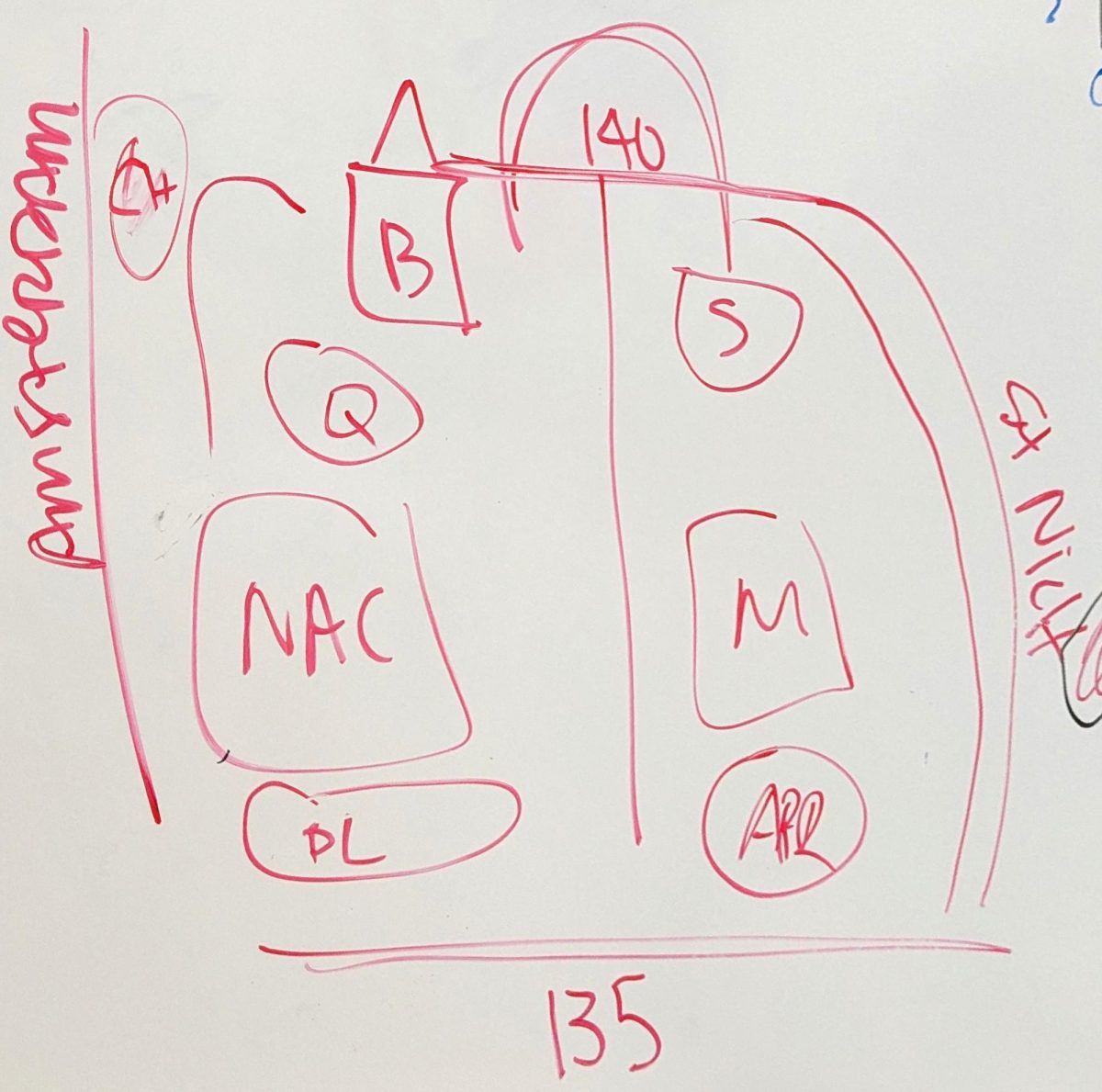

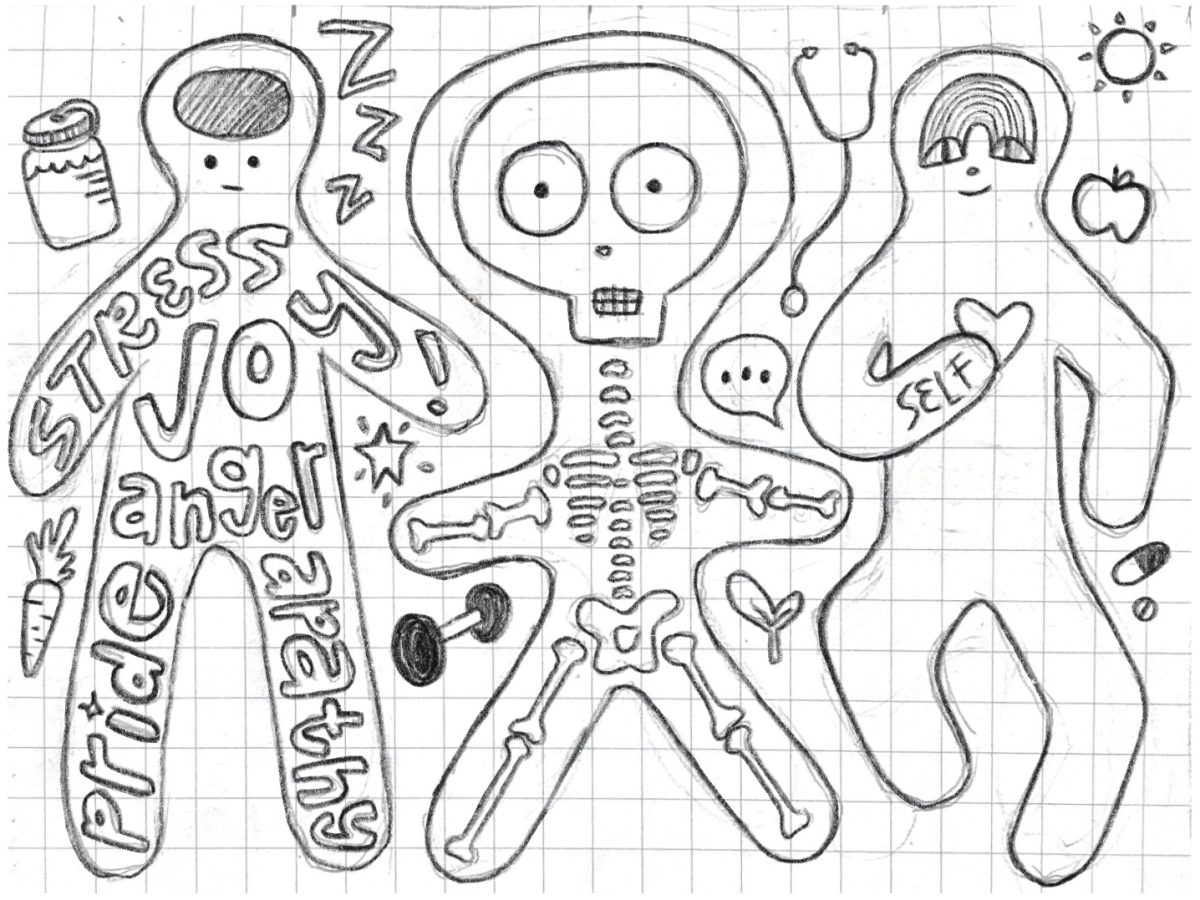

I surveyed HSMSE students and a few other Gen Z acquaintances about social media, politics, and mental health, yielding over 30 responses. About a third of respondents spent six or more hours on their phones per day; 16 felt “overwhelmed but unable to stop doomscrolling” at least once a week. When they selected various emotional responses to online political content, the most popular options were “disappointed” at 21, “informed” at 19, and “entertained” at 14.

When asked about their attitudes towards this discourse, survey respondents generally agreed that people voice their beliefs far more intensely online than they would in person. Charged rhetoric usually gets more engagement, and the anonymity offered by a screen allows users to feel more comfortable expressing their beliefs. HSMSE students had meaningful reflections on the phenomenon.

One anonymous student appreciated how the internet gave them access to political education: “At a time when I felt like I could never have any meaningful impact and had no greater purpose, I found meaning and intent in my largely dormant political views … Online media, when trustable and sourceable, has validated my beliefs and opened me up to learning more about society and even improving myself.”

Opportunities for learning and advocacy are at our fingertips like never before, but they do come with critiques. Astrid Clayton (’25) wrote, “The internet is more focused on ‘being a good person’ via reposting what everyone else does more than it supports nuance, centering relevant people’s voices, [or] thinking critically … I’ve noticed a lot of people reposting stuff along the lines of ‘you’re disgusting if you don’t do XYZ,’ rather than helping people do XYZ or spreading the message of someone personally affected.”

Many recent movements across the political spectrum have used social media to promote their messages, especially to engage youth. I don’t think this has uniformly pushed us in a progressive direction, as society might expect of the “rising generation”—rather, it has driven us away from each other and towards polarized, idealistic standpoints. Although some of my experiences in online leftist spaces have been similar to those in the first quote, I’ve noticed pervasive division and hypocrisy.

The progressive side of the internet continually wrestles with the idea of “performative activism.” This might call to mind the black square of June 2020, which 28 million users posted in solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement (I even recall one sixth-grade teacher presenting a black slide over Zoom). However, some activists criticized it for overshadowing the flow of information about the actual issue, arguing that individuals and institutions exploited it as an easy chance to feign support while ignoring underlying injustices.

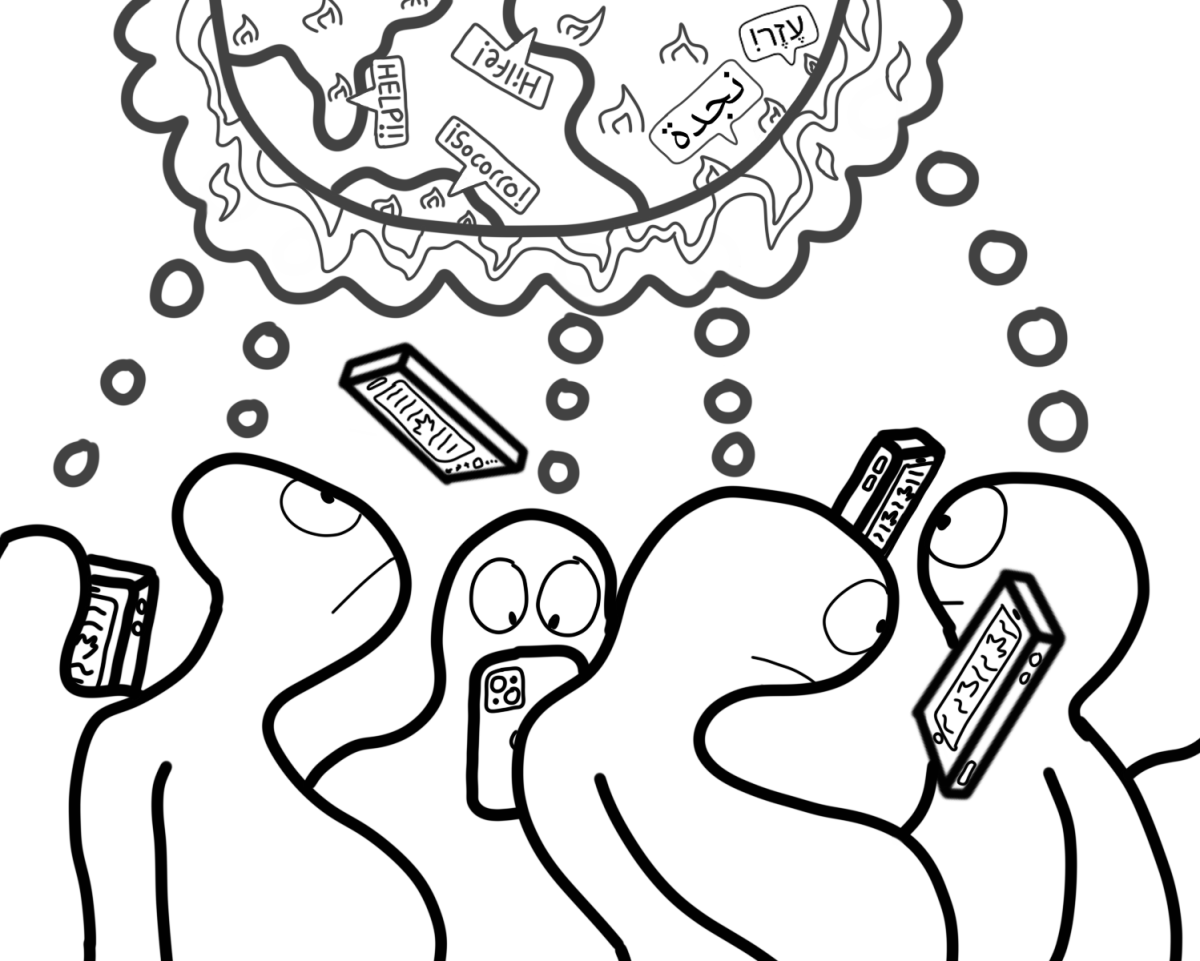

In June 2024, I came across an AI-generated image intended to raise awareness about the Israeli army’s bombardment of Palestinian civilians in Rafah. Shared over 46 million times on Instagram, it displayed a vast, rust-orange landscape of indiscernible rectangular objects (tents? trucks?) with “All Eyes on Rafah” in bold lettering. I saw some acquaintances who had never previously spoken about Gaza repost it, probably following suit from celebrities. But the picture lacked context about the crisis and had no call to action beyond blindly reposting. People’s eyes weren’t even on Rafah—just AI slop. As of April 2025, the city has become rubble.

The image also eclipsed Palestinian journalists documenting atrocities on the ground. Bisan Owda, for example, shares Palestinians’ stories of displacement, heartbreak, and resilience—starting each video with, “Hi, it’s Bisan from Gaza and I’m still alive.” Dominant Western outlets have displayed pro-Israel bias in their coverage: Writers Against the War on Gaza found that The New York Times quotes Israeli and American sources over three times more often than Palestinians. To me, Owda exemplifies how social media can provide an international outlet for suppressed perspectives.

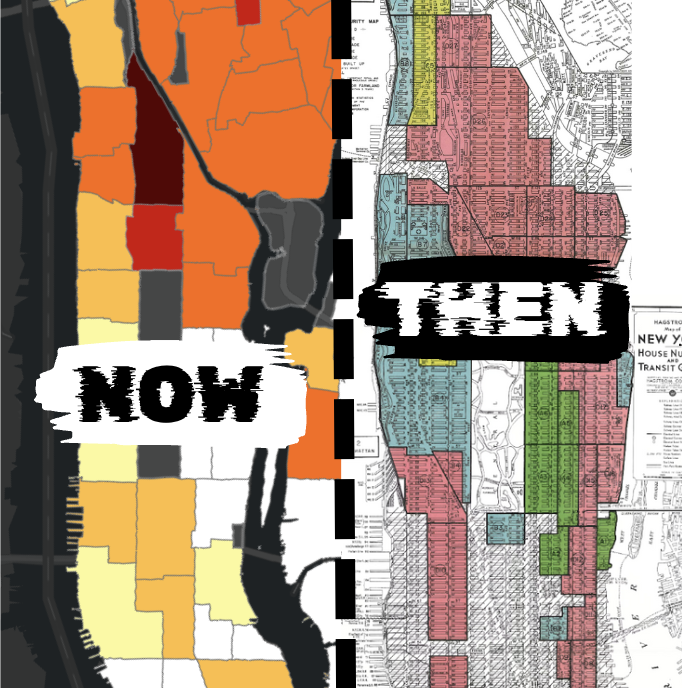

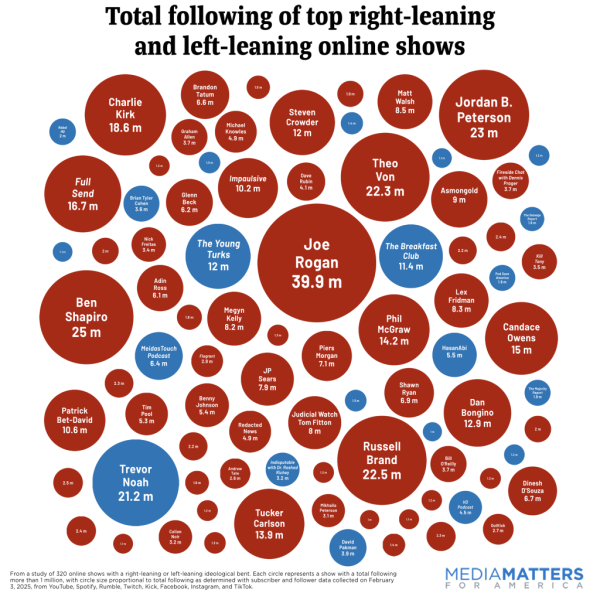

Overwhelmingly, though, the online media ecosystem favors conservative content. Media Matters for America found that right-leaning online shows had nearly five times as many followers and subscribers as their left-leaning counterparts, and “nine out of the ten online shows with the largest followings across platforms were right-leaning.” Furthermore, 72% of shows self-identifying as non-partisan were detected, in fact, to lean right. These findings reveal that popular media carries distinct political narratives that sway viewers’ beliefs, even if not immediately obvious.

One notorious example is the “alt-right pipeline”: a theory about algorithms’ manipulation of users’ beliefs as they interact with increasingly controversial content, leading them to extreme forms of nationalism and bigotry. The pipeline often targets young men struggling with loneliness and insecurity who turn to the internet for solace. Instead of getting the help they need, they idolize creators with lavish lifestyles and problematic yet alluring personas. Users become desensitized to prejudice, coming to embrace views like those of Andrew Tate: “You can’t be responsible for a dog if it doesn’t obey you, or a woman that doesn’t obey you.”

The effects of this pattern were exemplified in the 2024 presidential election. 49% of 18–29-year-old men voted for Donald Trump, as opposed to 37% of women in the same age bracket. The age group leaned the most Democratic overall, but these statistics reflect a concerning polarization likely inflamed by online content.

Tech billionaires, including Elon Musk and Mark Zuckerberg—the respective owners of X (formerly Twitter) and Meta—enjoyed exclusive seats at Trump’s second inauguration. Their platforms have played a key role in the spread of far-right rhetoric, influencing Americans at the polls.

Following Musk’s purchase of X in October 2022, the weekly rate of posts containing racist and anti-LGBTQ+ slurs rose by 50% in eight months, according to a recent study. Additionally, data reflects that bot activity might have increased (contrary to Musk’s purported goals). More recently, in response to Trump’s re-election, Meta revised its standards on hateful conduct to “allow allegations of mental illness or abnormality when based on gender or sexual orientation.”

Zuckerberg also ended fact-checking, while Musk has long spread misinformation himself. For example, in early 2020, Musk casted doubt on COVID-19’s danger; during the leadup to the 2024 election, he fearmongered about Kamala Harris “vow[ing] to be a communist dictator.” These claims are wildly inaccurate, but he enjoys a powerful platform and wide audience who might not immediately think to fact-check. Misinformation is rampant across the internet, distorting public knowledge about current events.

Trump’s influence on TikTok is notable as well. I remember panicking with my peers on January 19 when the planned ban went into effect—only for the app to be suddenly restored: “As a result of President Trump’s efforts, TikTok is back in the U.S.!” It felt ominous. Government insiders reported that the ban was especially motivated against pro-Palestinian content; the U.S. provides Israel billions of dollars in military aid yearly, despite 61% of Americans opposing it (according to a June 2024 CBS News poll). TikTok has not publicly stated changes to its guidelines, but some users did notice that the phrase “Free Palestine” and other similar postings were newly censored.

Billionaires have monopolized the digital landscape to control what we believe and how we spend our time. Instead of cultivating innovative spaces that connect people across identities and experiences, they have lured us into dangerous echo chambers that warp our understanding of the world and distract from tangible issues. For this reason, I believe the internet cannot be the primary setting of modern activism. This isn’t to discredit all online efforts—advocacy strategies do naturally evolve over time—but they are unsustainable when algorithmically censored and reduced to trends.

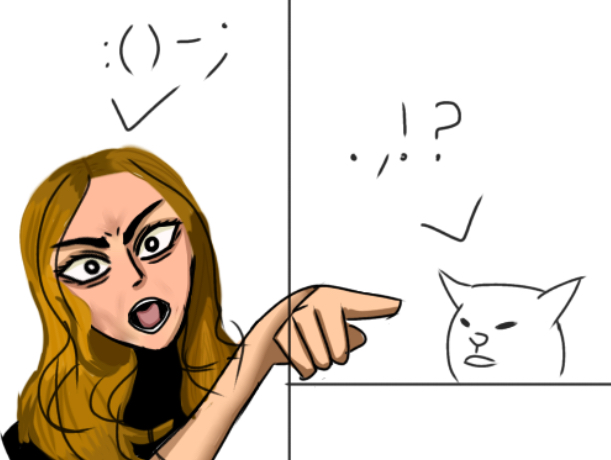

Although some bubbles of the internet might raise awareness for important issues, they fail to build productive, collaborative solutions. One survey respondent wrote that social media “has no way to teach a developing person how to debate or state their opinion legibly and accurately, nor can it prevent us from devolving into insults.” This aligned with what I often see online: People engage in ad hominem attacks instead of meaningful discussions.

We must learn to maturely engage with others’ perspectives and work for progress together, rather than explosively finger-pointing when our ideas are challenged. Simply speaking face-to-face can be a crucial start. Appreciating each other’s body language and other social cues allows us to—as Astrid Clayton put it—“acknowledge [our] shared humanity.” Respect and open communication are essential as we explore complex topics.

Our emotions around current events are real, which is why we need to direct them at systemic injustice instead of each other. Personally, I’ve found that protesting offers catharsis and reminds me that I am not alone, while doomscrolling plunges me into hopelessness and isolation. One anonymous, like-minded student articulated that “physical activism requires more effort and dedication. However, it can be more impactful, for the voice, microphone, and march will almost always beat a string of ones and zeros.”

Gen Z must join together—offline—to demand a liveable future. Protests can present risks and are not accessible to everyone, but there are many other ways to advocate, such as expressing ideas through art, getting involved with our communities, and donating to impactful organizations. The current political moment requires us to live with unwavering conviction. Will we stand on the right side of history or cower under its weight, blinded by blue light?