Chapter 1: “Doctor, What’s The Cure For This?”

Introduction:

“Doctor, what’s the cure for this?” It is a simple yet convoluted question that keeps us on the brink of pain and discovery. We might not know what goes on within our bodies on a microscopic level, but we understand our feelings, thoughts, and reactions. Like other species, we build defensive strategies and innate responses to situations over time, which can include developing long-term conditions. However, a primary characteristic that defines humans is the ability to conceal authentic emotion. But as we progress as a socioeconomic body, we start to realize that we aren’t programmed to be robots. We deserve to react and feel: natural rights that should be understood and morally accepted.

But what defines a human? And how can we choose to celebrate and uphold humanity? By definition, a human being is “a member of any of the species of the genus Homo, such as Homo erectus or Homo habilis, that are considered ancestral or closely related to modern humans.” Ironically, the definitions on which we base human thought and emotion are more complicated than we can imagine, yet understood completely through our feelings as individuals of free thought. However, navigating the path to help others can be tricky when one cannot find the tools to help themself: the current dilemma. Then the question becomes, could we afford to become solely solution finders or problem solvers?

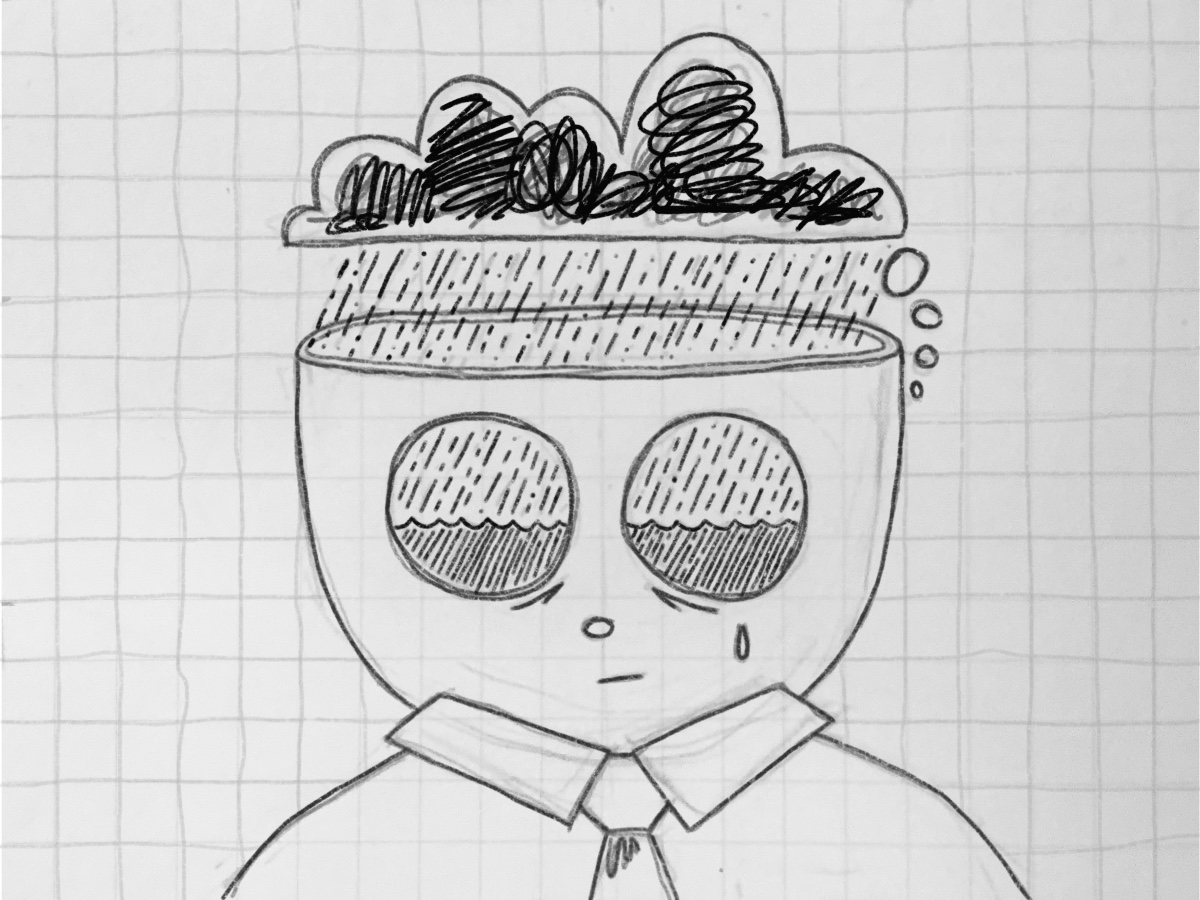

As agents of the human race, one may be defined under pain, family, love, matter, intellect, and identity. Our social identity (where we go to school, and who our friends are) subjects us to different growing environments: different soil, water, and nutrients. As simple as this may seem, the paradox does not necessarily lie in our ability to grow, but in our ability to persevere despite inhibition of growth. As living organisms, we have preferences and interests, and the reaction to the deprivation of these can constitute pain, which also makes us human. By the same token, given that depression and anxiety are disorders related to the cognitive reaction to trauma and pain, they are evidence of our humanity.

Trauma, a stimulus that can exhaust our brain, is a common cause of depression and anxiety, yet can be formulated by many different relationships and situations. No matter how much pain a human being can process, the catastrophe is nonetheless the same. The reaction to trauma can change over time, creating triggers that tie people to a traumatic event in the same way that we are emotionally bonded to our family, friends, and natural environment, thwarting their physical and mental flourishment and sprouting a negative perspective on the world.

In 2024, the younger generation has grown more comfortable and accepting of their identity. Yet, many still suffer from sexual trauma, conflict with religious figures on sexual identity, generational trauma, forced boundaries, etc.—these all have led to a general resurgence in depression and anxiety. The simple yet complicated way to communicate one’s needs in a dire situation would be to verbally say “I need help.” But before anyone can diagnose or propose a solution as a self-proclaimed doctor, one must identify the individual’s unique circumstances, and not confine them to generalized categories. Grouping different people’s experiences under a “common explanation” or “symptom” is more harmful because they are not receiving the personalized attention they need.

Chapter 2: “On A Scale of 1–10…”

As a student, I can objectively say that humans are intelligent creatures. We can adapt to difficult circumstances and adopt mindsets that can push us through adversity. Whether it’s through computational and practical analysis or persuasive theology and debate performance, there is a language through which we can communicate different topics and discoveries. We are also receptive and expressive of judgment—the majority of the population struggles with communication, and specifically with communicating pain, especially among demographics who are underrepresented and have low social status. Humans, undoubtedly, are competent at being smart, but also vulnerable, a skill that should be celebrated, not weaponized and scrutinized.

Vulnerability is the will to be confident and open about one’s setbacks and flaws to spread awareness of a widespread issue, or stigmatized phenomenon. As one processes pain and chooses to be vulnerable, there comes the challenge of how one connects with other people who are also struggling but might not be as willing to share their story. Then, we find ourselves asking, “How do you feel on a scale of 1–10?” to which the question’s subjectivity leads to generalizations about what someone is going through. Pain tolerance is as unique as our personalities, even though pain is a shared experience. People’s experiences can build up tolerance to pain, and that creates a bigger rift in our understanding of each other’s true experiences. As one person’s “9” is another person’s “3,” individuals resort to the simplicity of numbers and words such as “I’m fine” to avoid the true complexity of our minds and feelings.

Likewise, the paradox not only lies in how vast our interconnected network is compared to other species but also in how little we can fully understand each other’s emotions. A person who might need desperate help is met with a lack of resources and finds themselves internalizing their struggles as forms of weakness, pushing them into toxic habits and patterns of mental spiraling. Can we then fully know how someone is feeling? Does this make us unfit to help others? Like I said before, humans can adapt to difficult situations. As beings of communication, it’s important and necessary to normalize difficult conversations and continue to make space for people to come forth as they are. If people choose to disclose personal information and be vulnerable, we must sign a social contract and not use it against them but uplift them. Either way, being at our lowest makes us susceptible to the greatest change.

Our brain is more powerful than a supercomputer, able to generate calls and responses in a matter of seconds. It can allow us to mirror human interaction and empathize with human experience through tiny mirror neurons and dendrites. Yet, our minds can be so delicate, rendering us paralyzed physically and metaphorically. Fear, likewise, is a paralytic, and a lifestyle under that state can affect one’s work, school life, and more. One switch, or “trigger,” can allow for a catalyzed flow of negative emotions and chemicals, and the human body must react to survive. As triggers become witness marks of trauma, the smallest stimuli can allow for moments of “fight or flight,” and identifying those glimpses that make our body react can help us find the best antidote or cure if there is one.

Chapter 3: “I Have Your Results”

Well then, what is the cure, “doctor?” There might not be a be-all and end-all cure for mental health struggles, but there is a mindset that allows people to have hope in their own journey and still see tremendous progress. When facing dilemmas, the human mind goes immediately to “avoiding conflict” mode due to the exhaustion of being self-conscious. Our thoughts are not analyzable, so the “mindset” cannot come from somebody else, it has to be self-reinforced. The ability to say “I need help” is equated with being burdensome or worrisome, evidence of our “people-pleaser” nature. Although we may not understand what makes us tend to self-deprecate to medicate, reinforcing positive self-talk is another key to trusting ourselves, and keeping ourselves grounded as we trust others with our story. When interacting with other individuals, some converse with logic and some converse with emotion. Individuals that are masters of their own story can fully see it through to the end, and find meaningful lessons looking back.

We also must distinguish between a cure and a coping mechanism. Sometimes, habits that we use to “deal” with an issue that we face, whether it’s related to anxiety or depression, are not actually solutions but evasions. As we grow into these unhealthy habits, the problem never actually gets addressed, and the bandage itself rips. Our inability to fully face the thoughts we avoid makes us underestimate ourselves and overestimate the problem at hand. Then comes the “fix it” mentality, which pushes individuals to simply move on without having full closure.

Cognitive impairment and behavioral disorders related at the core to anxiety and depression were once thought to be precursors of serious mental conditions like schizophrenia. While some people may benefit from noninvasive treatments like talk therapy, many cases end in overmedication, which can contribute to lifelong psychological trauma, impersonal communication, and even physical deficiencies and long-term substance dependencies.

Even in cases where therapists are austere in their approach, a shift in direction could be a step in the right one. With the right people in place, one can identify the root of their trauma. Many struggle with the question “What scares you?” because while everyone has natural fears and anxieties, it’s still difficult to pinpoint specific events that have induced these fears.

Nonetheless, some diseases are a constant fight, and running away from this fight is a mindset that we must absolve. Unfortunately, while every diagnosis has common symptoms that can be explained with a simple Google search, depression and anxiety are situational. Some of these mental disorders can be inherited via epigenetics as well, which, unfortunately, are out of our control. Our body reacts to protect itself, which is the foundation of intuition. We know what works for us and what doesn’t. As humans have learned to live with other species through millennia, we can learn to live with our anxieties and fully celebrate the human experience as vocally as possible.

Conclusion:

Ultimately, a person denying someone of their own experience is a testament to society’s unwillingness to foster sympathy within itself. It contributes to the epidemic of internalization and forces those around us to contribute to the silence that renders the voice powerless. The human voice is the unit of our individuality, clarifying intentions and magnifying feelings. Our voice is how our bodies maintain homeostasis, and deprivation of a homeostatic interaction or expression is ultimately damaging emotionally, socially, and psychologically. With today’s media landscape, this stigma has only been fed and even more internalized. How are we so ashamed of our individuality, flaws and all? Perhaps our society has redefined humanity based on perfection, conformity, and judgment.

With the unfortunately high costs of healthcare and clinical processes for diagnosing and treating mental illness, some have continued to use their platform to spread the word through factual evidence, research, and down-to-earth verbal communication in hopes of fighting mental illness. Two sides of the fight have sprouted and it’s up to us to decide which side wins—silence or self-awareness. As an individual trying to implore mental health conversations among generations that are indifferent to the topic, I am confident that those who do speak up will advocate for those who cannot advocate for themselves. Only then will we undeniably acknowledge the ebb and flow of mental health.