When you first think of segregation, you might think of its definition: “the action of separating people, historically on the basis of race and/or gender”. Or, for those who pay attention in history class, you might remember a lesson about Jim Crow laws and the Reconstruction era. However, even if you know absolutely nothing about segregation’s effects on our country—which is doubtful, but supposedly possible—I don’t blame you. Especially in New York City, segregation is a topic that receives little recognition from both politicians and ordinary citizens. According to a poll conducted by Manhattan Institute, it’s not a main concern for almost all 2025 NYC voters, with participants’ primary concern going to crime and public safety (49%), housing costs (29%), the economy (28%), and immigration (22%). And because segregation is so overlooked, it permeates every corner of the five boroughs, unbeknownst to most New Yorkers.

To understand how New York City still suffers from a deemed “past” atrocity, you have to travel back in time to the 1940s and the Great Migration—the mass movement of Black people from southern states to northern states. African Americans living in the South were desperate to escape oppressive Jim Crow laws, which left them vulnerable to racial violence, denied them economic and educational opportunities, and promoted extreme segregation. This migration of millions gave New York the largest Black urban population in the world. Sounds familiar? (Hint: It’s likely because it’s a mandatory part of the school curriculum.)

On the other hand, what a lot of people don’t know is that Jim Crow laws still existed in the North. The widely known court case Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) legalized “separate but equal” racial segregation not just in the South, but in the entire United States. As a result, Whites-only apartment buildings, hotels, restaurants, and even American Airlines seats were present in New York and many other northern states. To put it plainly, almost nothing changed for the African Americans who had moved; discrimination was prominent throughout all states of America.

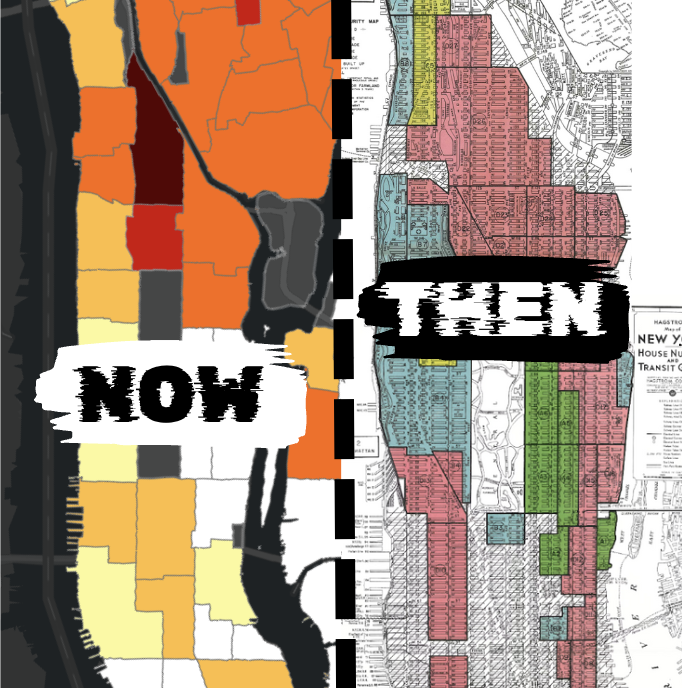

In addition to Jim Crow laws, the Great Depression brought out an even lesser–discussed discriminatory practice: redlining. The Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC), which was created to help people keep their homes, started classifying NYC neighborhoods to decide which people were eligible for mortgages. People who lived in “fourth grade” or “hazardous” areas didn’t receive any mortgages from banks. Not surprisingly, the quality of a neighborhood was largely based on how many Black people (or people of other minority races) were already living there.

DISCLAIMER: Image includes outdated and offensive terminology.

Redlining allowed White people to live in “nicer” neighborhoods for less money, essentially forcing minority races to move to “worse” neighborhoods (since they had to pay full price, and cheaper homes were in underdeveloped and overcrowded areas). These divides throughout the five boroughs ultimately morphed NYC into what it is today: the ninth most segregated city in the United States. This is incredibly problematic, as segregation promotes inequality and deepens racial and societal tensions among different groups. In a city that’s known for being a “melting pot” of ethnicities, we can’t afford to limit our cultural diversity by square mileage.

Despite how little people discuss it, the fact that New York City is highly segregated isn’t concealed in the slightest. Many people critique NYC’s education system for allowing students with better resources—who are typically rich, White, or both—to get into top schools. Even HSMSE, a school more diverse than most, has a Black student population of just 8.5% and an economically disadvantaged student population of 39%, which fails to match the 19.5% of NYCDOE students who are Black and 73.5% who are economically disadvantaged (read “Racial Disparity at HSMSE and Beyond” for more information about racism in schools and STEM). Or, if you want to experience the direct effects of redlining yourself, go to Manhattan and walk 15 blocks from 86th Street to 101st Street; the differences in both who and what you see are startling.

But if segregation in NYC is so obvious, why doesn’t anybody speak about it? The sad reality is that systemic racism is so embedded into our society’s history that people accept it as the norm. It’s present everywhere; people often look up to and worship the upper-class, often assuming that they’re well-off only because they worked harder than their peers, and therefore deserve to hoard their resources. Neighborhoods stay segregated due to social preferences, as minority groups might feel more comfortable in communities where they share cultural backgrounds, languages, and values. Families of minorities that don’t have the privilege of generational wealth are deemed as hopeless or “bad examples” because they never had the chance to break the cycle of racial inequity. The pattern of contentment perpetuates systemic disparities that people in power largely fail to address, which is why nothing has changed to this day. It’s impossible for segregation to lessen if no one is fighting against it—which is quite the predicament, because integrating New York could very likely fix many other problems citizens are more concerned about.

The issues most discussed among NYC voters (crime, housing, employment, and immigration, as already mentioned) would be significantly reduced if people recognized the impact segregation has on all aspects of life. Having a balanced ratio between all races and groups of people would allow for equally distributed economic and educational opportunities among all neighborhoods and communities. For those who lack quality education and are economically disadvantaged, integration would allow for better schools across New York City, not just in areas like the Upper East Side or Midtown. This would encourage students to finish their education, which would lower dropout rates, therefore dropping crime and poverty rates as well. Taking measures to eliminate unfair laws that hurt minorities would help build stronger, more resilient, and stable communities. And, without the disparities caused by segregation, demand for housing would go down, and more equitable property values would be available to all members of society.

It should be noted, though, that progress isn’t linear, and the exact outcomes of integration cannot be calculated by hypotheticals. Plus, whether or not minorities would be willing to integrate is unpredictable, since there hasn’t yet been a direct course of action taken by the government to reduce the effects that segregation has had on the country.

Clearly, segregation is a complex issue with many different layers to it. Deciding the best solution to tackle it isn’t necessarily black and white, and it’s going to take time to achieve a fully integrated society. There are definitely steps we’ve taken to indirectly address this problem; for example, reforms in education and community safety have already started to make progress in reducing disparities across our city. But if we don’t start recognizing segregation as a real and current problem—not just a piece of history—the ghosts of America’s past will continue to haunt us in the future.