Whenever there is a big fire, or a “job,” firefighters start shouting “JOBTOWN!” as a part of getting ready to go to work. Ideally not the most common exclamation, “JOBTOWN!” was yelled a lot in Los Angeles County in January, with the many major fires there. Who could have seen this destruction coming? There were only myriad warning signs. Much of California goes up in smoke every year, and the amount of land turned to ash has been rising for years. The Los Angeles area fires are indeed tragic, yet not a huge surprise; Los Angeles County should have been more prepared.

To start, the people affected by these immense fires need help badly. The destruction caused, largely to houses and forests, is estimated to cost around $50 billion to repair. The American Red Cross and Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) are both active in the Los Angeles area, providing food, water, and shelter to those affected, and we can help their efforts by donating. There have already been dozens of deaths confirmed, and the death toll is likely to continue rising as Cal Fire crews continue to search among the rubble. What could have been done before and during the fires to mitigate their damage and risk? Why did they grow so large so quickly? What can be done in the future to protect Los Angeles—and everywhere in the country—from future wildland and brush fires?

The Eaton Fire, a bit north of Pasadena, CA, burned over 14,000 acres, an area not much smaller than Manhattan—it was not even the biggest fire in Los Angeles County. That grim title falls to the Palisades Fire, located a mere 25 miles west of the Eaton Fire and burning over 23,700 acres: around 1.6 times the size of Manhattan and almost 90% of the size of the Bronx.

The seemingly obvious answer to the first part of this question is to send more firefighters to the scene of the fire. But which fire? With two immense fires on their hands, state and local fire departments in Los Angeles County had to pick one to focus more on. The Palisades Fire posed a greater threat to human life, so any triage assessment would dictate that it would be the wise one to start with. In any case, simply sending more firefighters was much easier said than done. The president of United Firefighters of Los Angeles City Local 112, Freddy Escobar, said that the money needed to adequately staff the LAFD wasn’t there because of recent cuts to the department’s budget. Thus, there were not enough firefighters.

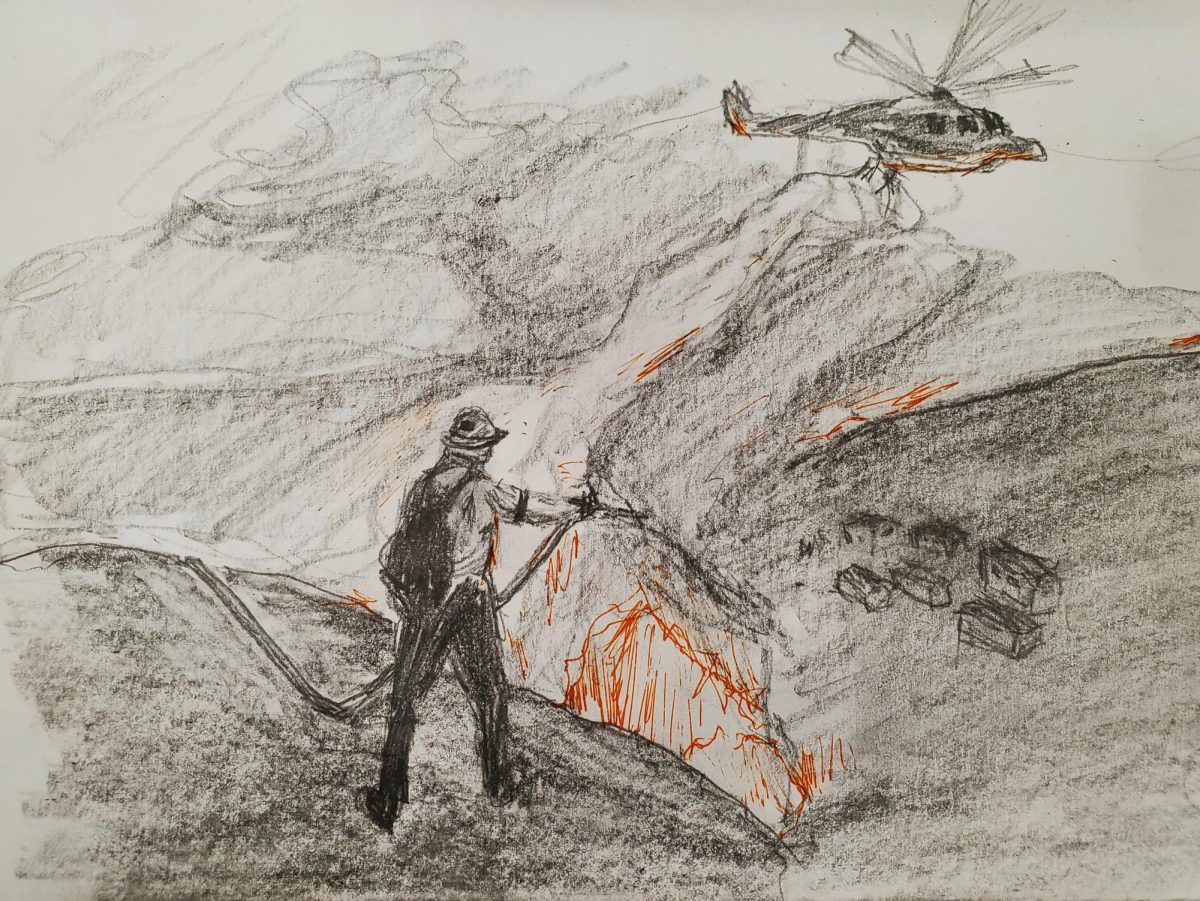

The second, seemingly obvious answer would be to put more of the wet stuff on the red stuff (put more water on the fire). The issue here is that wildland firefighting is very different from city firefighting. Wildland firefighting is mostly done with a shovel. Because wildland fires are typically so large and ferocious, getting water on them is a fool’s errand. Add to that the ridiculous hikes firefighters need to take to even get to the perimeter of the fire, let alone the seat of the fire, and suddenly the idea of lugging hoses into the job doesn’t sound so practical. Hose is heavy, after all. Because of this key difference from city firefighting, wildland firefighting relies much more heavily on manpower. The more shovels are in the ground, the quicker gaps in the foliage, called firebreaks, can be created, hopefully stopping the fire’s spread in its tracks once it reaches that point.

Another problem the various firefighting agencies faced with these two fires: wind. There was wind gusting up to 100 miles per hour in some areas. These conditions not only made the fire more dangerous and the fire suppression operations more dangerous, but required significantly wider firebreaks, further straining personnel availability. Even then, the wind might have gusted just at the right time and blown an ember across the firebreak, making all the work that was just done all but useless.

The wind made dumping water onto the fire more difficult as well: The water could be blown away into a spot where it does nothing to suppress the fire. Lastly, water resources in Southern California are infamously sparse. This certainly didn’t help firefighters in the slightest, since water is the most common material used to extinguish fires. Due to the locations of the fires, a lot of the already limited water resources had to be diverted to city firefighting or many of the structural blazes the wildland fires caused.

Essentially, any seemingly obvious solution against Los Angeles’ raging wildland fires is, to say the least, impractical. Perhaps all we can do is wait it out and pray that not too much is damaged—life, property, or otherwise. But there are some potential answers to future wildland fires that can be adopted by Los Angeles, and the rest of the country as well.

First, increased staffing. Many fire departments across the country are understaffed, with about 82% of them being largely or entirely volunteer. This means that there is no guarantee that any given incident will have adequate resources to even be battled at all, due to volunteer firefighters responding individually from wherever they may be rather than from firehouses. This poses additional challenges to firefighting operations. In Los Angeles specifically, there is less than one firefighter per 1000 residents. This level of staffing is very low, and according to LAFD officials, would require 62 new firehouses to meet recommended benchmarks. How can staffing be increased? Why, through city and state funding, of course. Funding fire departments all across the country would be a critical first step to making our country’s fire service more efficient and better prepared for anything that may come their way. Of course, funding also aids with training, which is also a critical component of preparedness.

Second, water resources. If there were less water consumption for frivolous purposes in the United States, particularly in the often bone-dry Southwest, more water would be available for firefighting. But since this is firefighting we’re talking about, let’s hope for the best and prepare for the worst. Assuming water consumption carries on as it is, there are still a few things that can be done to abet water shortages, making future fires potentially less catastrophic. One is somehow coming up with a way to draft and desalinate water from the ocean in one fell swoop, which would pretty much solve the problem in coastal areas. But for non-coastal fires, the other method would be to construct a system of cisterns, or underground water storage tanks, to catch rainwater, which could be done in two ways. 1: The cisterns are positioned strategically throughout the city to make fetching water easier if the hydrants run dry; in this instance, tankers would be essential components of the fire department. 2: The cisterns feed directly into the water mains, which would not only alleviate the consumption issue, at least for long enough to develop fallback systems, but also make them directly connected to hydrants. More water in hydrants means lower risk of dry hydrants, which means less reliance on chance and more certainty that things will go as they are supposed to.

Los Angeles County and the State of California should have prepared for this twin conflagration to happen at some point—after all, California as a state overall is known for burning up every year. However, they didn’t have enough staff or water, leaving Los Angeles County with two massive conflagrations that decimated communities, instead of a fire that could be contained relatively quickly. Lack of preparedness is an important part of why the Palisades and Eaton Fires were so destructive: They simply couldn’t be mitigated or suppressed quickly enough or well enough. Funding fire departments is the main way to fix that issue to prevent such a disaster from happening again, and this should be adopted nationally. There is simply too much at risk.