“Do You Have a Destination?” Mac Miller asked in a song from his posthumous album, Balloonerism. The question felt familiar. Since I entered high school, I have been asking myself, “Do I know where I’m going? Does anyone else here know?”

According to interviews, Miller had his heart set on being a musical artist by the time he was 15, and he pursued this goal until the end of his life—and in a way, after as well. But for many of us the future is not as clear. Only a certain number of careers and pathways seem apparent based on our STEM curriculum, and if none of these strike you, you are lost. Yet there are an infinite amount of careers that are not simply science or math.

I reached out to four people working at the intersection of the humanities, science, and technology to see what might be possible and to help HSMSE students realize that we are not held back by a choice we made at age 13; the paths available are as vast as our creativity.

Ambika Kamath, a behavioral ecologist and evolutionary biologist, left academia to co-found Liminal, a science communication collective that explains science for the public; J. Kenji López-Alt is a chef and author whose recipes and techniques derive from his background as an MIT-trained scientist and architect; Alondra Nelson earned a Ph.D. in American Studies before serving as deputy assistant to President Joe Biden and acting director of the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy; and Bill Prady worked as a software designer and computer programmer before co-creating a successful TV show about physicists, The Big Bang Theory.

In speaking to them, a common thread emerged: Science is a method of looking at the world and figuring out how things work, and understanding people is both the heart of the humanities and essential to accurate and responsible science. Nothing in this world can ever truly be understood using one or the other, but a delicate mix of both is necessary for those who want to have an impact on the world.

Ambika Kamath moved to the U.S. from India when she was 18 to study biology at Amherst College in Massachusetts. She then went on to earn a Ph.D. in Organismic and Evolutionary Biology from Harvard University. She has always been focused on bringing a feminist perspective to her work: Her lab at the University of Colorado was called FLAIR (Feminist Lenses for Animal Interaction Research Lab), and focused on animal behavior science through a feminist lens. But after several years, Kamath moved onto a new project, Liminal, which helps scientists explain and share the work with the public. Last May, she ran a virtual workshop with medical students in the Effective Science Communication course at Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, which taught participants how to examine the story of their journey in science and connect with an audience by crafting compelling narratives.

When we spoke, Dr. Kamath talked about what communication between scientists and the public has looked like in the past, and how it should look in the future. The science community now, she said, often thinks that only facts need to be communicated to the public to understand new findings, when really, a broader approach is necessary: “We are also social, cultural, political beings, and we have this broader context into which science fits and we’re going to make decisions based on making sense of all those different parts of our lives together.” Viewing complex concepts through one lens isn’t possible in the scientific world, or in any world.

J. Kenji López grew up in New York City, not so far from HSMSE. His father was a geneticist, and López-Alt entered MIT planning to be a biologist but soon changed his major to architecture. In his sophomore year he took a job as a waiter and realized he wanted to work in cooking. After jobs at several restaurants around the university, López-Alt began writing about food.

He has published several books, including The Food Lab, which is a NYT bestseller and has received many awards. His books and column at the blog Serious Eats explore the best way to create a dish or meal, using scientific methods. When asked if he thinks the art of cooking clashes with the fact-based nature of science, Lopez-Alt responded, “There’s art to science and science can be applied to art. Science is a process: It’s a tool we use to help us understand how things work. Art is an application: It’s the expression of thoughts and ideas to others in a way that makes them understand your perspective or makes them rethink their own perspective. It takes science and technique to be able to bring what’s in our head out into the real world where it can be shared.”

López-Alt is a self-described nerd, and he says he learned to love his nerdiness by finding other people with similar interests—at camp, online, and college. In fact, he’s not even MIT’s only graduate who is a professional cook. He actually got one of his first cooking jobs due to a recommendation from a professional chef who had also attended MIT.

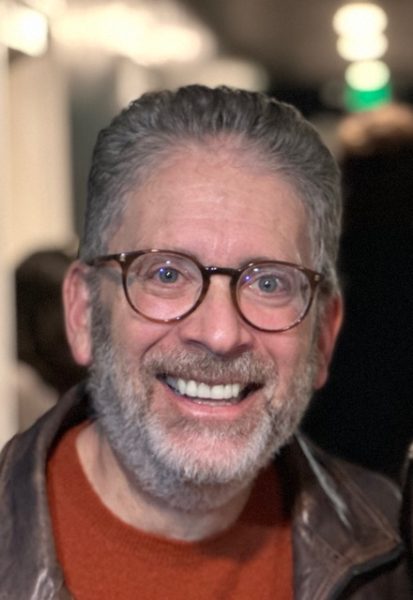

Bill Prady understands the skill of using every part of yourself in your work. Prady worked as a computer programmer and owned a successful software business before he began writing for television. His first job doing so was on the HBO series Dream On in 1995, and one of his early shows was related to his experience with computer programming, called Family Computing TV. He later began working in Hollywood, where he met Chuck Lorre and became co-creator on The Big Bang Theory, a sitcom about a few nerdy scientists and their experiences living together. The show includes a lot of advanced science thanks to Prady’s extensive research and a few professional scientists who fact-checked the material. The equations written on the numerous white boards were always accurate. In fact, in one scene from the show, the equations created by a UCLA professor for the show were actually the answers for an upcoming test for his students. The professor had brought his class to the show’s taping, but the students were so excited to be there that none of them noticed, Prady said.

Prady dove deep into the science included in his show and made sure he had at least a basic knowledge of everything he wrote about. He believes, “The more you know about how the world works, the better your art is. If you want to have a conversation between characters about the meaning of life, you want different points of view. If one of those points of view you want is somebody who studies existence from a scientific point of view and somebody who studies existence from a religious point of view, I need to know enough physics and enough Buddhism to write that conversation.”

Even though Alondra Nelson got her Ph.D. in American Studies, she was chosen by Joe Biden to be acting director of the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy. Her books—including DNA: Race, Reparations, and Reconciliation after the Genome and Body and Soul: The Black Panther Party and the Fight against Medical Discrimination—incorporated both sociology and science and impressed the White House enough to ask her to advise the president on scientific policy as one of his deputy assistants. Her tasks as a White House appointee were not purely scientific, but also incorporated civil rights, including developing a people’s Bill of Rights for automated technologies and a national strategy for STEM equity. Dr. Nelson is now a professor at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, where she offers an innovative perspective to the social sciences for students. Working at the intersection of science and humanities, Nelson expressed an outlook similar to Kamath: “For the world of inquiry and discovery, you need to bring your whole self. It is very old fashioned to have to divide the sciences from the humanities.”

All of these incredibly talented professionals have managed to incorporate both the sciences and humanities in some way into their profession and were kind enough to share their stories, for which the Echo is extremely grateful. Their paths demonstrate that no one in the HSMSE community should fear pursuing their passions, as none of us is solely a “humanities person” or a “STEM person.” We are all multifaceted, complex individuals, and can (and should) use every resource available to explore and find our passions and careers.