Have you noticed the disproportionate representation of racial groups in our community? It hasn’t always been this way—HSMSE was founded partly to confront historic inequities in specialized high schools. The issue extends far beyond New York City: STEM fields cater primarily towards white and Asian students and workers. This article is a two-part deep dive into racism’s impact on both our school system and the STEM industry at large in order to increase awareness and close the gap.

Note on DEI

Much of this article was written prior to President Trump’s suppression of DEI (Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion) initiatives in his second term.

His executive order, “Ending Radical Indoctrination in K–12 Schooling,” has placed a strong emphasis on patriotism in schools, especially in history classes. It has banned teaching students about “White Privilege” and “unconscious bias,” stating that an individual’s status as privileged or oppressed is not based upon their “race, color, sex, or national origin.” This executive order also removes protections for transgender students by preventing educators from supporting them—even through simple usage of the correct name and pronouns. It attempts to erase the existence of trans people and censors the undeniable history and current state of racism in our country, actively forcing educators to teach falsehoods. However, details of the policies’ enforcement are largely unclear.

The Trump administration has directed all federal agencies to put employees in DEI offices on leave, and changed references to race and gender on government websites. It has also threatened to strip federal funding from academic research to which race and gender are considered even remotely pertinent, including HIV and malaria research, due to their disproportionate effect on targeted communities. Even though Trump only has direct power over federal agencies, countless private companies, such as Apple, Target, and Meta, have ended DEI programs in response to the political climate; tech giant Google notably removed Pride and Black History Months from its calendar app. Trump’s executive orders are already being blocked by courts, but they have significant ripple effects across the entire country.

Racial Disparity at HSMSE

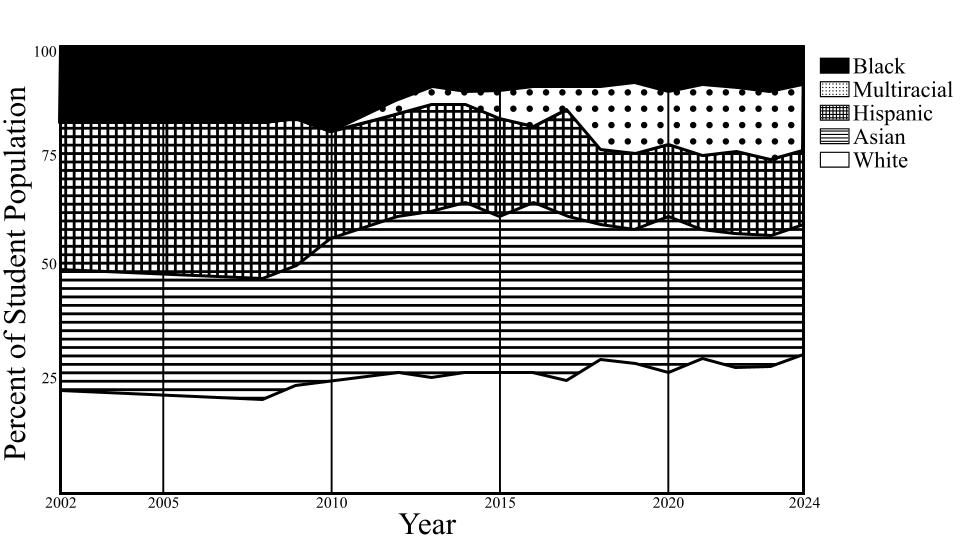

HSMSE’s racial diversity has long distinguished it from other schools. Whereas New York’s elite high schools have historically catered towards privileged groups, we were founded to better reflect the diversity essential to our city; in 2012, The New York Times named us the “least segregated” school across the five boroughs. But since then, Black and Hispanic students have become less represented in class demographics, while white and Asian students have become the majority racial groups—reflecting a trend in the STEM fields we advance to after graduation. Although HSMSE is still quite diverse as compared to other specialized high schools, many people are upset at the change.

The DOE aims for them to “reflect the diversity of New York City,” but it largely fails to uphold this mission. In 2024, the incoming freshmen at specialized high schools overall were 52% Asian and 26% white, despite these two racial groups only making up a combined 32% of all NYC public school students. These disparities are not the fault of families who make up the majority, but a consequence of racism’s entrenchment in our society: The system makes quality education unfairly exclusive and pits groups of people against each other as they seek the best opportunities.

The three oldest specialized high schools—Stuyvesant, Brooklyn Tech, and Bronx Science—especially lack in diversity. The percentages of Black, Hispanic, and Indigenous students combined fall below 15% at all of these institutions. Stuyvesant admitted only 10 Black and 16 Hispanic students into its class of 744 freshmen for the 2024–25 school year. Native Americans are often overlooked: They make up 1.2% of NYC DOE students, but from 2014 to 2021, they only received an average of 0.5% of specialized high school offers.

White students are the second-largest racial group across the three schools, while Asian students make up over half of the student body. Asian Americans often face intense academic pressure as a result of the “model minority” myth: a stereotype that they are innately hardworking and intelligent as to prosper in white-dominated spaces. This overlooks the scope of anti-Asian racism and forces Asian people to conform to harmful, unrealistic expectations, while implying other people of color aren’t as worthy of success. It is important to note that the label “Asian” should not be treated as a monolith as it encompasses a variety of ethnicities and experiences with oppression.

All of NYC’s students deserve equal access to a rigorous education. HSMSE was established in 2002 for those underserved by legacy institutions; the NYC Schools and CUNY Chancellors at the time worked together to further enrich the experience with access to CCNY’s campus. They founded our school alongside the High School of American Studies at Lehman College and the Queens High School for the Sciences at York College. Additionally, HSMSE’s location in Harlem strategically connected it to a vibrant Black community in order to promote representation.

At least in the beginning, these efforts marked HSMSE on the map as an exemplar of racial and socioeconomic diversity. The New York Times recognized us in 2012 as the “most diverse” school in New York City, with a student body that was 32% Asian, 25% white, 24% Hispanic, 19% Black, and 0% Native.

As of 2024, however, HSMSE’s racial statistics have shifted to 31% white, 29% Asian, 16% Hispanic, 14% multiracial, 9% Black, and 1% Native students. White students have become the majority racial group at our school, with 18% fewer Black and Hispanic students as compared to 2012. Although HSMSE is still significantly more diverse than the older specialized high schools mentioned previously, many are disappointed by the change. Diego Benitez (‘26) found it “sad … part of the reason why school is so fun and interesting is because of all the different people and the experiences that they’re able to [share].” Meanwhile, total enrollment has increased from 405 to 555 students over the years. Some members of the HSMSE community theorize that as our school’s popularity has grown, its diversity has decreased. Siona Lewis-Coffey (‘25) reflected, “As the school has become more well respected and well known, it’s lost some of its MSE charm.”

Critics of the specialized high school admissions process often take issue with the SHSAT, the score of which is the sole factor determining a student’s acceptance. Many believe the exam discriminates against marginalized racial groups, students with disabilities, lower-income New Yorkers with less access to test preparation, and English learners (the test is not offered in other languages).

In 2019, former Mayor DeBlasio attempted to abolish the SHSAT and instead admit the top 7% of students from each middle school, but the plan received pushback: Some communities who greatly valued the SHSAT as a gateway to educational empowerment felt attacked. Other racial justice advocates thought reform should first be focused toward K–8 schools. Ultimately, the proposed measure never gained traction. In 2022, current Mayor Eric Adams proposed creating new specialized high schools in each borough that use other admissions criteria, but he has not followed through with any official policy changes.

The Discovery Program is an integration measure that did pass, ensuring low-income students who scored right below the SHSAT entrance cutoff for a certain school can still attend if they perform well in a summer course. Each specialized high school reserves 20% of its seats for Discovery students. Also, Int. No. 175 has been proposed in the City Council to “require the Department of Education to publish a report on access students have to SHSAT preparation.” “Issue Spotlight: Making the SHSAT More Fair” was featured in Issue 10 of The Echo and discusses the bill in more depth.

HSMSE once had a Middle School Initiative specific to our community that encouraged local Harlem residents to apply here. It was led by former Principal Dr. Crystal Bonds, former Assistant Principal Wiley Burgan, and Mr. Dolcy, who was the other assistant principal at the time. The program ended when funding declined as a result of COVID-19; currently, Principal Dolcy is seeking support from local politicians to relaunch it.

All of these efforts are certainly steps in the right direction, but Black, Hispanic, and Indigenous communities are still grossly underrepresented at prestigious high schools—which then feed into elite colleges and universities. Unfortunately, the trend is a reflection of life post-graduation.

Racial Disparity in the Workplace and STEM Fields

Black, Hispanic, and Native individuals are not only less represented in STEM schools, but also in the STEM workplace, often as a direct result of the lack of diversity in education. Despite Black workers making up 11% of the overall American workforce, they constitute only 5% of the engineering field. Hispanic communities show an even greater disparity, making up 17% of the overall workforce and only 8% of all STEM jobs.

Indigenous Americans are rarely included in these conversations, because they make up an even smaller percentage of the industry—less than 1%—despite being 2.9% of the general American population, though statistics vary. Only 20% of schools on Native American reservations even offer tech classes, further limiting access to STEM education and later career opportunities. Tara Astigarraga, an Indigenous woman working in STEM, said, “When people talk about activities in STEM or how to build pipelines and get people involved, they typically talk about the Black and Hispanic communities and even women. But Native American communities hardly ever get brought up because when you round that data, we get rounded to zero and we don’t even get included in those conversations.” Many of the studies we cite in this article did not include Native people: This was not an intentional omission, but rather further proof of Astigarraga’s point.

We corresponded with an anonymous EEO (Equal Employment Opportunity) professional, who also emphasized the importance of focusing not only on the raw numbers, but how these minority groups are represented across workplace hierarchies and in leadership positions: “You have to look not only at the entity as a whole but also at different administrative, professional, [and] executive levels and see the areas that need more diversity.”

This skewed representation is cyclical. Many people (including employers) grow to associate positions with certain demographics. Hiring managers have been found to display biases favoring more “American” names and against names that may be indicative of non-white candidates, regardless of the rest of an applicant’s credentials.

Pursuing a career in STEM might not even occur to many members of minority groups, as they don’t see themselves already represented. A lack of access to resources—such as internet, education, and extracurriculars—also impacts many individuals’ access to jobs: Almost one quarter of Black students in the U.S. still do not have reliable, high-speed internet in their homes. A lack of support from educators is also an issue: 80% of 6th–12th grade math and science teachers in 2017–18 were white, while only 7% were Black and 8% were Hispanic.

After they’ve been hired, members of minority groups often experience difficulties advocating for themselves and having their work acknowledged, and are forced into boxes and feel isolated. Companies making efforts to improve DEI have attempted to address this. The EEO professional we spoke with explained the concept of “retention”: Companies, in an attempt to retain their employees and ensure their comfort, provide opportunities for them to “participate in mentoring programs, get raises and promotions, and feel included. Most places have something called Employee Resource Groups or something similar where individuals of a certain race can meet and discuss challenges people face as a group or ways to work together to provide more opportunities and encourage recruitment.”

Underrepresentation of Black, Hispanic, and Native people in STEM leads to lack of consideration in design and in research. Products are often built by people who fail to consider their own internalized racial biases. Something as simple as an automatic soap dispenser can struggle to recognize dark skin tones simply because dark-skinned people weren’t considered in the design process. Similarly biased datasets have been used in other human recognition software, including the automatic brakes on self-driving cars. With STEM’s importance to daily life, inadequate representation of so many demographics can cause significant detriment to product quality.

This disparity has been a well-known issue in the medical industry for a long time. Only 5.2% of doctors in 2022 were Black, compared to 14.4% of the total population in the U.S. Physicians from a 2007 study were twice as likely to underestimate Black patients’ pain, leading them to be given incorrect diagnoses or treatments. A 2016 report shows that Black people are far less likely to receive the proper medication, or to receive any at all. Naturally, Americans of color don’t trust a healthcare system that was not designed with them in mind. In 2000, when asked to rate both their trust and satisfaction with their physicians on a scale of 1–5, Black and Latino patients gave their physicians an average of ~0.3 points less than white patients in both satisfaction and trust.

The trend of white and Asian people being overrepresented in fields like engineering and medicine is not only problematic for underrepresented groups. Because Asian Americans are considered a “model minority” group and are highly represented in STEM fields, it is often assumed that they don’t face racism in the workplace or in the hiring process. This is not remotely true. Asian people also face name-based discrimination, and often grapple with similar difficulties as other racial minorities after being hired. A 2023 study found that 36% of Asian American professionals say they have “experienced racial prejudice at their current or former companies.”

This belief also discounts the experiences of those who have underrepresented Asian identities: It is generally accepted that there are six primary ethnic groups in Asia—although that’s a somewhat arbitrary metric—and there is no official distinction between them in statistics involving race. This view of all Asian Americans as a monolith means that underrepresented Asian ethnicities—such as Southeast Asians—are grouped in the same category as the most prominent Asian racial groups in STEM: Indian and Chinese Americans. A 2021 study at the University of Buffalo found that “Filipino students were nearly 60% less likely to choose a STEM major than other Asian American subgroups,” and “More than 70% of the parents of Chinese, Indian, and Sri Lankan students attained a graduate degree, which was double the percentage of Vietnamese and Thai parents who received graduate education.”

When an individual is a part of multiple marginalized groups and thus faces discrimination from multiple directions, a new, unique type of oppression is experienced; this concept is called intersectionality. Asian American women are especially marginalized: They are 46% less likely to major in a STEM subject than Asian American men. When they do break through in STEM positions, Asian American women face increased marginalization as a result of their intersecting identities, often dealing with sexual harassment and assumptions about their skill level.

This is the case for many women of marginalized racial groups in STEM, and as such it is impossible to examine the factors of race and gender independently of one another. One commonly cited statistic in feminist spaces is the gender pay gap: the fact that women make 85¢ to a man’s dollar. In 2019, it was found that Black and Hispanic women’s salary is only 55.2% that of Asian men, and only 63% that of white men (see Pew Research Center graph). This issue is not unique to women and people of color: LGBTQ+ people and disabled people also experience wage gaps of varying degrees, especially when identities overlap.

Many companies have taken steps to improve these issues with DEI initiatives (note that many of these are being shut down due to Trump’s recent executive orders). The EEO professional stated that many companies are diversifying their hiring processes by ensuring that they’re hiring from a wider range of sources—this includes an increased focus on HBCUs, community colleges, groups of Black and Hispanic engineers, and high schools with CTE (Career and Technical Education) programs. Many of these initiatives have faced backlash for focusing on hiring based upon minority status rather than on merit. This criticism assumes overrepresentation only occurs because certain groups are more qualified, fails to consider other factors that contribute to the lack of diversity in a given field, and assumes that those who have received lower-income education do not have the proper qualifications.

Other companies have attempted to increase their diversity by “hiring blind.” This means removing any identifying information from resumes (such as names and addresses) that may indicate the gender or ethnicity of an applicant. This way, hiring managers ignore unconscious biases that may arise in the early stages of the hiring process, and they focus more on the qualifications of the applicant. While this strategy is successful at addressing unconscious biases from hiring managers, it does not address the systemic issues of underrepresentation in education or lack of resources.

What now?

The change starts here. HSMSE was founded on the belief that diversity is a valuable foundation for our community, and it is essential that our academic institutions work to reflect this ideal. Diversity in education allows students to expand their perspectives and contribute to a more just world after graduation. Creativity, innovation, and equity are the cornerstones of our society, but they must extend across the breadth of human experiences. This endeavor is more relevant than ever as the Trump administration cracks down on DEI. As we innovate for a more technologically advanced and socially just world, we must confront systemic injustice and uplift the experiences and ideas of all.

![[ERROR]: Lack of Women in the Software Industry](https://theechohsmse.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/APC_0280-984x1200.jpeg)