Sometime in 1931, a shipment of elm lumber made its way from France to Cleveland, Ohio, destined to become veneer finishes on high quality furniture. To the surprise of the recipients, the trees were crawling with spore-carrying elm bark beetles. The beetles wiped out many of America’s elms — over the course of the next 59 years, an estimated 75% of the 77 million elm trees on American soil died. The spores in question were produced by sister fungi Ophiostoma ulmi and Ophiostoma novo-ulmi, and the infection they cause is known as Dutch elm disease (DED). Unfortunately, the most common and culturally significant elm in the states, the American elm, was especially susceptible to the fungi, leaving streets barren and shadeless.

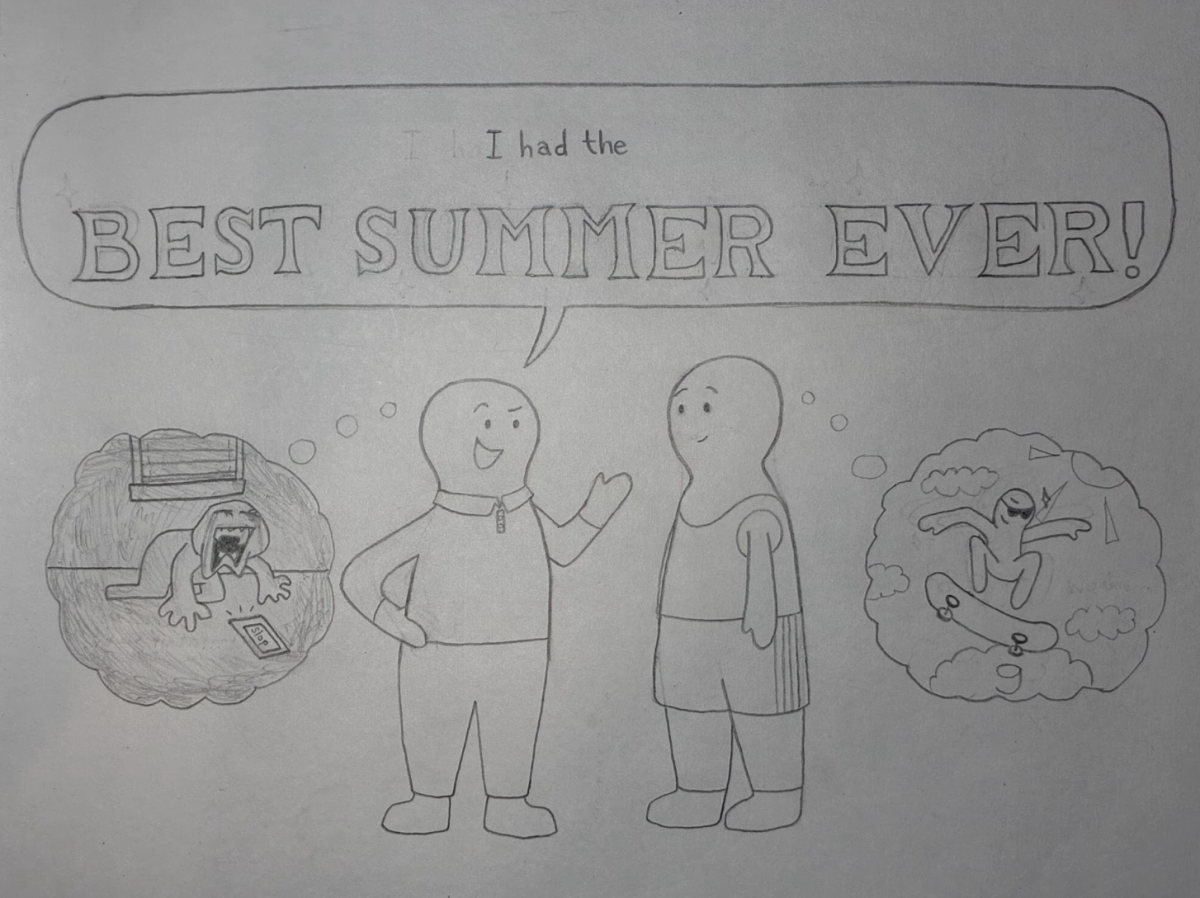

In typical government fashion, the response to this crisis was rushed, poorly thought out, and more expensive than it needed to be. The proposed solution was to clone male specimens of common fast-growing trees (e.g. maples and oaks) — the resulting clones would always be male, avoiding the litter of fruit that female trees produce, and the clones would quickly replace elms due to their shorter life cycles. What the government failed to consider was that first, fast-growing trees die faster and therefore require more frequent replacement (and more money invested), and second, only propagating male trees drastically increases atmospheric pollen levels. The imbalance between male and female trees also meant that a smaller percentage of produced pollen would actually go towards pollinating trees, and there’d be more free-floating pollen that could irritate people’s allergies and respiratory conditions.

In the early 2000s, while coming up with a system for ranking plants by allergy level, horticultural epidemiologist Thomas Leo Ogren coined a term for the problems caused by thinking of female trees as nuisances: botanical sexism. And since the “fewer female trees = less litter” idea persists, the high pollen counts continue, with TIME reporting that children living at least 10 years in the US have higher rates of asthma (which can be caused by increased particulate pollution) and pollen allergies.

There has been controversy regarding the theory of botanical sexism, with some scientists arguing that it only applies to certain trees or that the imbalance isn’t severe enough to make a difference. The former complaint doesn’t have much validity to it, though — Ogren agrees that only some trees contribute to the problem given that only some trees are dioecious. Dioecy is the quality of each individual of a species having a certain sex (some can fertilize while some can produce offspring), as opposed to monoecy, which is used to describe species where each individual can carry out both fertilization and production. Since only some tree species have sexes, only some tree species can have unbalanced ratios of male to female. Even if the argument is that some male trees contribute more to the problem than others, of course that’s true! Different species of trees produce different amounts of pollen depending on size, distribution, and pollination method, but that doesn’t change the fact that the ratio of males to females is uneven. The controversy comes down to whether heightened allergic reactions in America are a placebo effect, but the science seems to say that isn’t the case. That being said, if the theory of botanical sexism does prove true, your allergies can be partially blamed on the elm bark beetle x Ophiostoma ulmi collab and the government’s half-baked solution.

![[ERROR]: Lack of Women in the Software Industry](https://theechohsmse.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/APC_0280-984x1200.jpeg)